William Scott is an artist for whom the particular carries a special significance. It is not just his ability to capture the essential qualities of the subject, but his facility to make that subject speak to us beyond its known parameters that makes his work so satisfying and continually interesting.

As a genre, still life was important to Scott from his earliest days, and indeed some of his most acclaimed work throughout his long painting career conjures complex and fascinating compositions from the simplest of articles.

The summer of 1976 was one of the hottest on record in Britain. At Scott's rural retreat, an old farm outside Bath and deep in apple and pear growing country, his magnificently espaliered pear tree bore a splendid harvest and for a period through that autumn and winter its fruit became his sole subject. The group of paintings, known collectively as 'An Orchard of Pears', came together with a remarkably constant vision, one which would be clear when they were first exhibited the following year.

The canvases in the series are rarely large, and even by Scott's standards have pared down the compositions to an absolute minimum, allowing the artist to concentrate completely on the fruits at the heart of the image.

On plain coloured backgrounds, sometimes the white of a tablecloth, sometimes the green of grass, and with the occasional prop; a plate or bowl, maybe a knife, we find pears. The painting itself is spare, a thin outline to delineate the pear and to add the stalk, the colour simple and unmodulated. In some examples the colours are not even related to those of an actual pear. Yet throughout the series, Scott manages to not only make his pears feel absolutely pear-like, but he enables them to speak further to us.

As objects of contemplation they offer thoughts on the wider world of nature; the growth, the renewal and the fruitfulness. Unlike an artist like Euan Uglow who liked to portray his fruit as it decayed over time, Scott's pears retain that delight in the freshness of the just picked that every gardener knows.

The painting itself is spare, a thin outline to delineate the pear and to add the stalk, the colour simple and unmodulated. In some examples the colours are not even related to those of an actual pear. Yet throughout the series, Scott manages to not only make his pears feel absolutely pear-like, but he enables them to speak further to us.

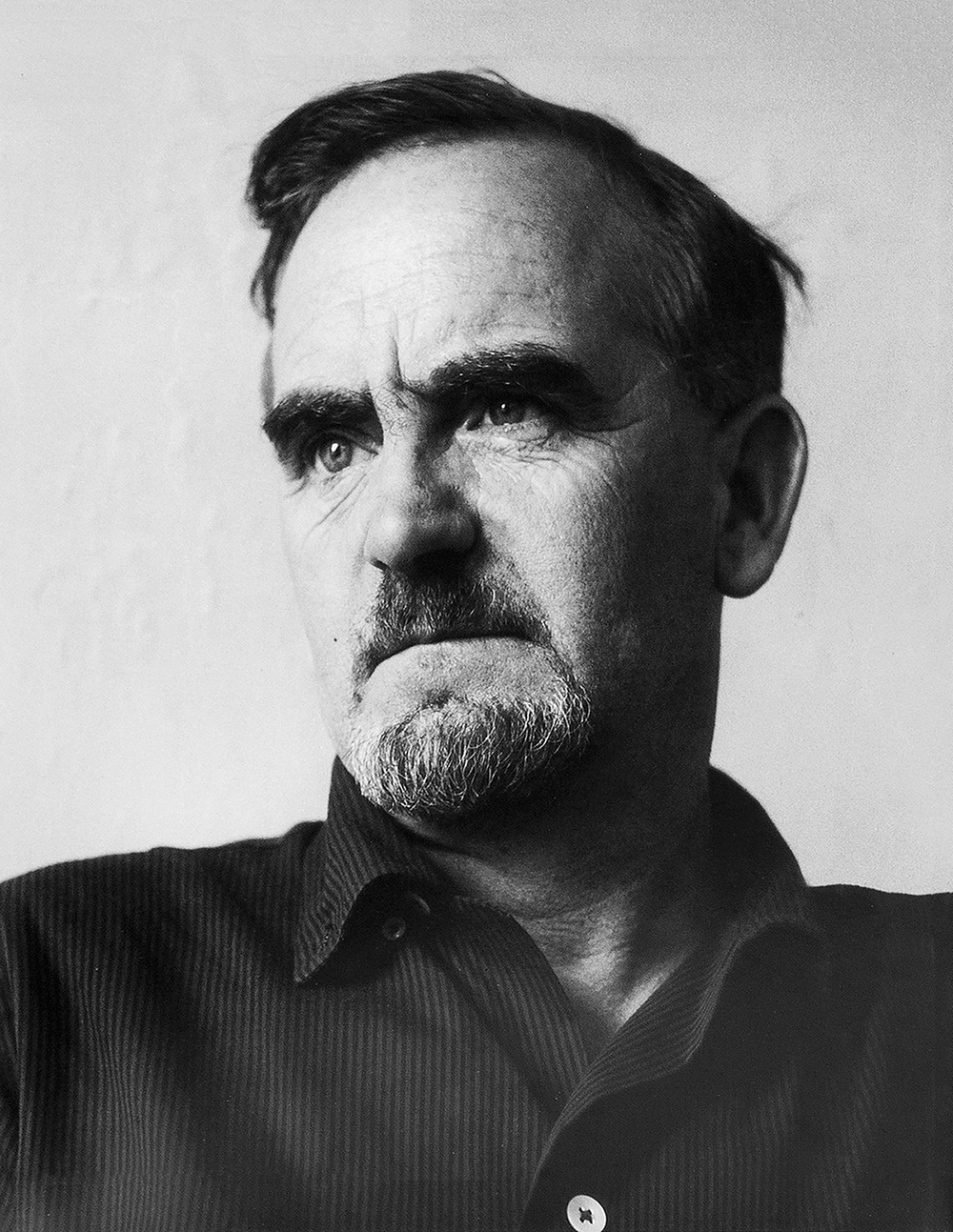

Photo: © James Scott

That the paintings go beyond their obvious subject was clear very soon. In the summer of 1977 a group of paintings from 'An Orchard of Pears' was included in an exhibition at Liverpool's Walker Art Gallery, curated by Edward Lucie-Smith, Real Life. In his catalogue text, Lucie-Smith sought to differentiate between two basic strands of representational art as practiced at the time.

Some artists - the minority - seem to think of art as the creation of a an individual system of symbols, which stand for what has been observed. William Scott's pears, for instance, are hieroglyphs rather than representations. Others - the majority - seem engaged in an effort to bring what is seen and what is put on a canvas closer and closer together, without denying that seeing and painting are in fact different activities.

Lucie-Smith pushed this analogy further with his short poem in the catalogue which he dedicated to William Scott and Erik Satie, a nod to the composer's composition, Trois morceaux en forme de poire. Whilst we might wonder as to the extent to which a pear as painted by William Scott might be a hieroglyph, it is clear that the artist was able to imbue an image such as An Orchard of Pears, No.5 with something beyond its plain description of the subject. There is perhaps a Proustian quality to Scott's pears, an ability to meld a nostalgic reminiscence with our own understanding of the subject, and to then present it in a way which is uncompromisingly modern.

Unlike an artist like Euan Uglow who liked to portray his fruit as it decayed over time, Scott's pears retain that delight in the freshness of the just picked that every gardener knows.

Pears had featured in Scott's work from the first. His 1935 Still Life (Private Collection), his first extant foray into the genre, featured them prominently, and they return to his canvases across the years. Some commentators, notably the poet and friend of Scott's, T.P.Flanagan, have drawn somewhat tenuous correspondences between the pear as a symbol of fruitfulness and a form of erotic innuendo, but it is an inescapable and rather poignant story from the artist's later years that best illustrates the significance of the subject.

By 1986, Scott was still working, but was increasingly showing signs of the Alzheimer's Disease that coloured his old age. James, the artist's younger son, would sometimes assist his father by laying out a canvas and materials in the studio. On one occasion, Scott's attention seemed to be fixed on a pair of pliers on his workbench. James left him to work, but in his return found a small but finished painting of a single pear. Scott had himself returned his attention to the pliers, and the painting was to be the last he produced.

References

1 - Edward Lucie-Smith, in Real Life, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool 1977

2 - We might draw a comparison here between Satie's attempt to give his musical pieces a quality of pear-ness and the famous request by John Lennon to The Beatles' producer George Martin to make Lennon's voice on Being for the Benefit of Mr Kite! 'sound like an orange'.