The sculptor Barbara Hepworth (1903-75) and the painter Pierre Soulages (b. 1919) were friends and artists who shared an interest in Tachisme. Hepworth was drawn towards the art movement in the latter half of her career, whilst for Soulages it has proven to be a lifelong preoccupation.

From their respective avant garde beginnings, both Hepworth and Soulages enjoyed considerable successes, exhibiting across the world, earning recognition, plaudits and numerous honours. Both artists have museums in their home towns dedicated to the display and understanding of their works. Hepworth, of course, has the Barbara Hepworth Museum in St. Ives as well as the Hepworth Wakefield; the Musée Soulages in Rodez was established in 2014, somewhat unusually, during the artist’s lifetime.

In 2019, solo exhibitions of the artists’ work happened to coincide in Paris: Hepworth’s first solo exhibition in the capital was held at the Musée Rodin, whilst Soulages’ 100th birthday was marked with a retrospective at the Louvre (a rare honour for a living, contemporary artist). Besides these parallels, Hepworth and Soulages had much else in common and the fascinating intersection of their lives, careers and interests is the subject of this essay.

Paris was a complete exhilaration after 21 years. And the happiest & most carefree moment for 21 years! I had a good time with Charles Lienhard, [Marcel] Joray, [Michel] Seuphor, Arp & Soulages - & I worked v. hard at the foundry. The large bronze is finished. [1]

In 2019, solo exhibitions of the artists’ work happened to coincide in Paris: Hepworth’s first solo exhibition in the capital was held at the Musée Rodin, whilst Soulages’ 100th birthday was marked with a retrospective at the Louvre (a rare honour for a living, contemporary artist).

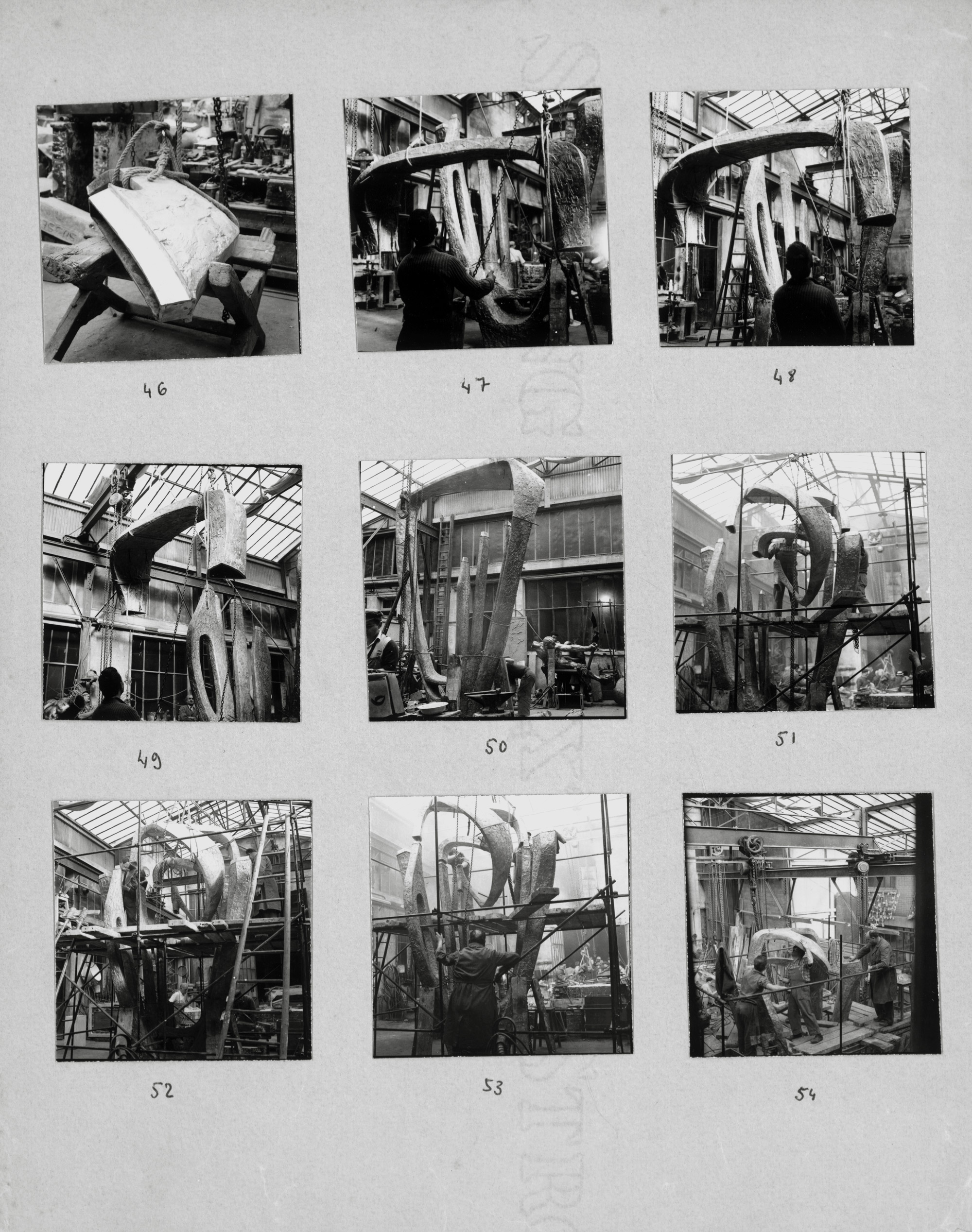

Fig 1

Meridian in progress at the Fonderie Susse Frères, 1959

Hepworth Photograph Collection

© Bowness, Hepworth Estate

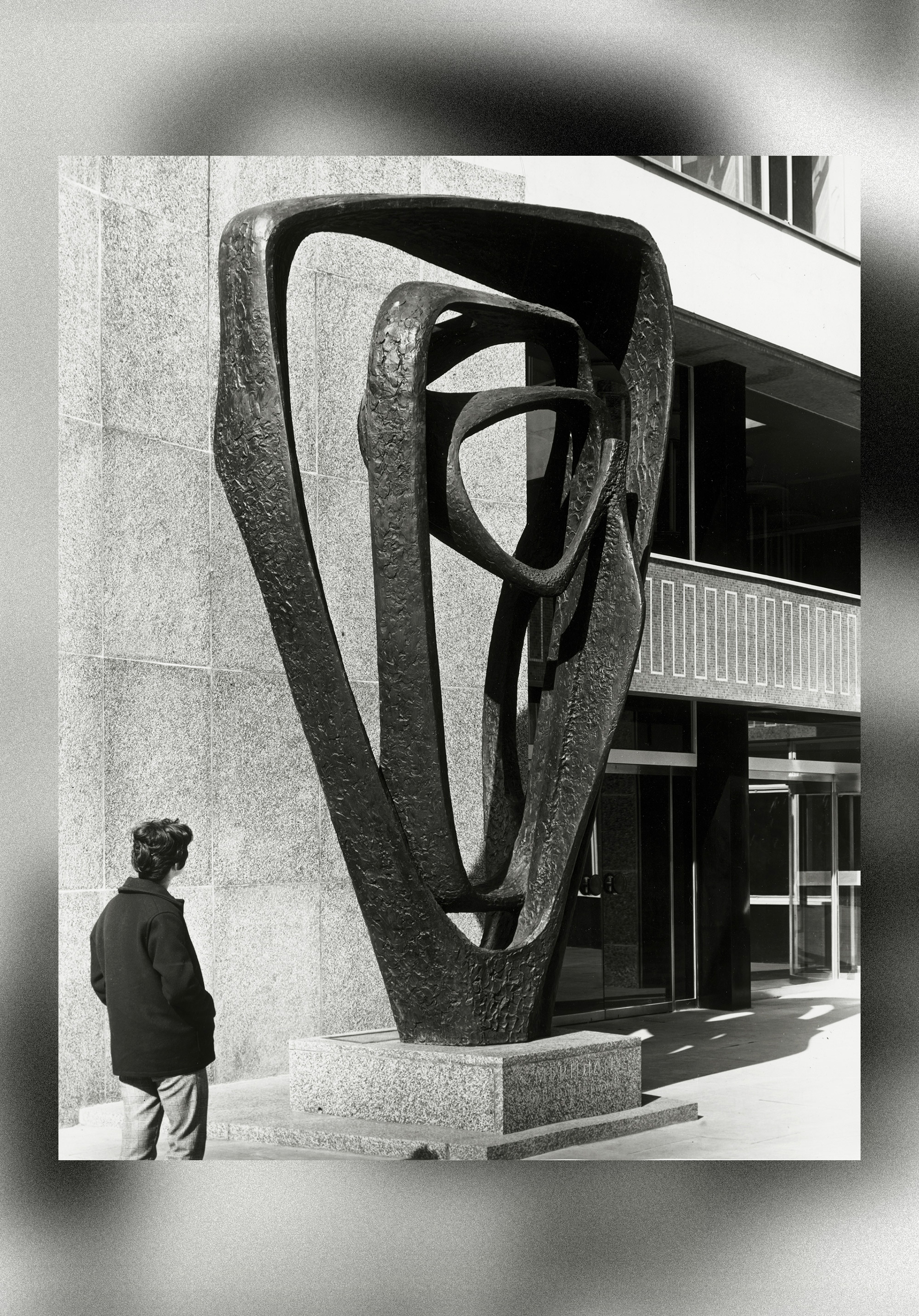

Writing to Herbert Read in December 1959, Hepworth described the excitement she felt during what proved to be her last trip to Paris. As well as spending time with friends – including Soulages – Hepworth was actually in Paris that November to oversee the completion of her first monumental bronze sculpture which was cast at the Fonderie Susse Frères at Arcueil (in the southern suburbs of Paris); the ‘large bronze’ she mentioned was her Meridian, Sculpture for State House, 1958-60 (BH 250), and one feels her excitement and satisfaction, and not a little sense of relief, that the hard work was over and that the sculpture was finally finished (fig 1). To celebrate, there was a cocktail party at the foundry on 12 November 1959, hosted by M. and Mme. André Susse, to which Soulages was invited. [2]

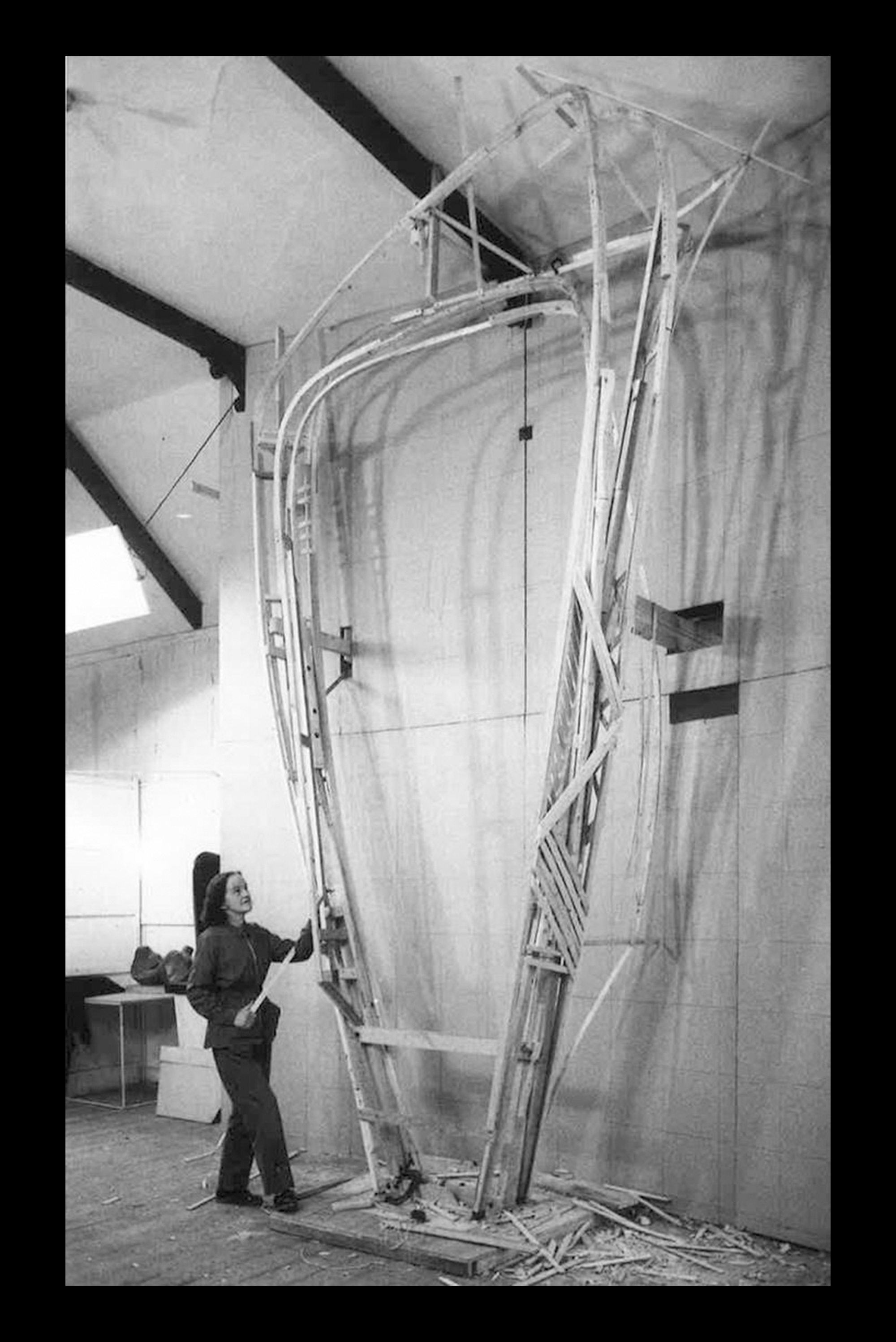

Hepworth only began to re-use bronze in 1956, having eschewed the practice of modelling clay figures for casting in the 1920s, and the completion of Meridian was a significant moment for her not least in terms of its technical achievement. Meridian, at 4.6m tall and about 3m wide, marked a substantial leap in size and scale for Hepworth. It was a major public commission for a new building in a prominent urban location (State House on High Holborn in London). [3] The prototype for the unique cast had already demanded a great commitment of time and labour even before the complex plaster for the ‘growing form’ was transported from St. Ives to the foundry in Paris. [4] Photographs of Hepworth’s process taken in the specially-rented studio space over the winter of 1958-59, document the spirit of invention combined with practical engineering necessary to build a wooden skeletal structure before layers of hessian and plaster could finally be added (figs. 2 & 3). [5]

Hepworth only began to re-use bronze in 1956, having eschewed the practice of modelling clay figures for casting in the 1920s, and the completion of Meridian was a significant moment for her not least in terms of its technical achievement.

Fig 2

Hepworth with the first stage of the prototype for Meridian, December 1958

Studio St Ives / Butt 650

Hepworth Photograph Collection

© Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Fig 3

Hepworth with the second stage of the Meridian prototype, January 1959

Studio St Ives / Butt 676

Hepworth Photograph Collection

© Bowness, Hepworth Estate

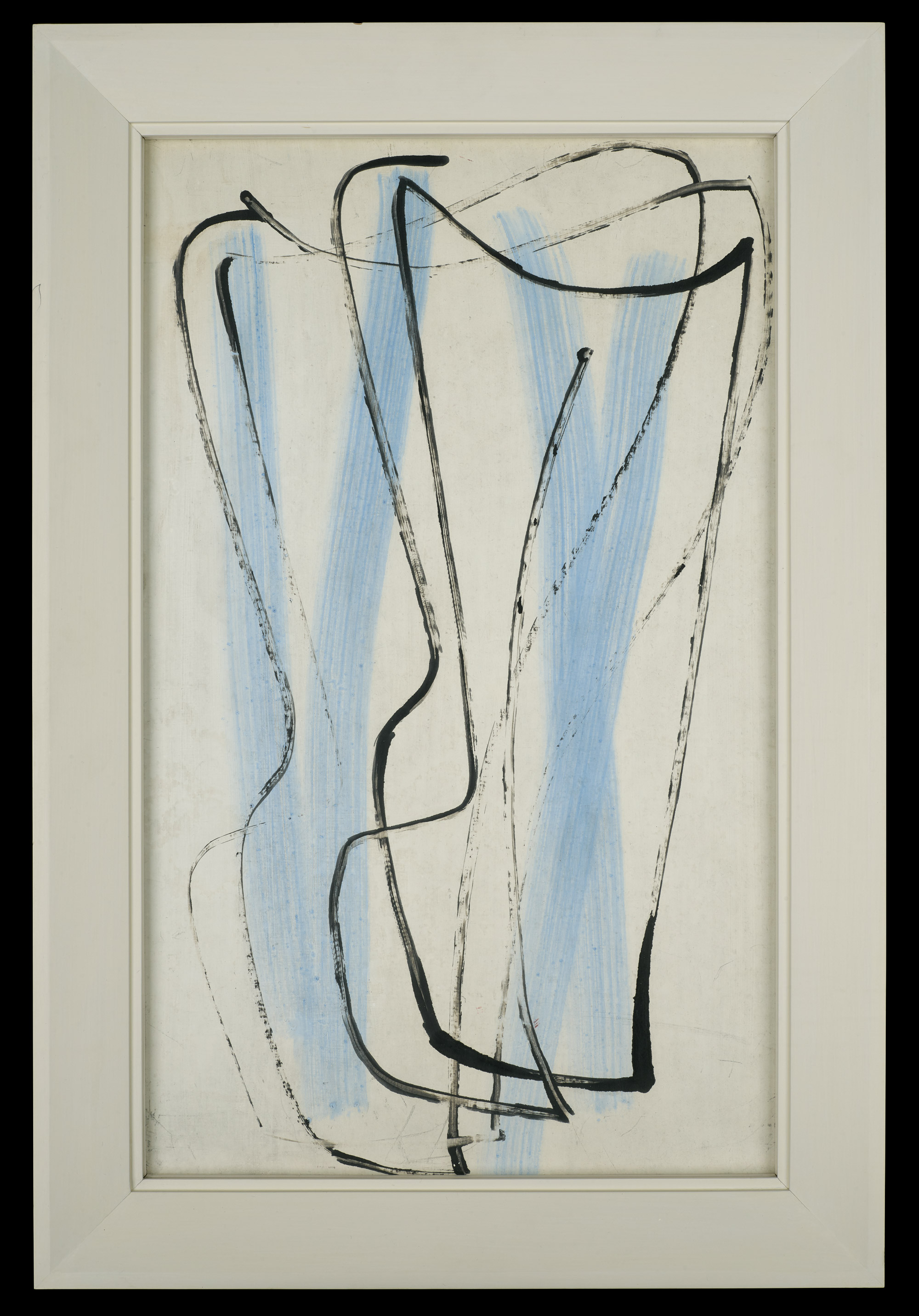

There is a fascinating correlation between Hepworth’s work in two and three dimensions at various points during her career, but the synergy is perhaps most keenly felt in this period, notably, for example, the painting of Torso (1958) and the series of Torso sculptures made the same year (fig 4). Whilst Hepworth did not draw directly for sculpture, she often explored ideas on paper or board which might later be investigated three-dimensionally in stone, wood or bronze. Conversely, Hepworth might also revisit the concept for an extant sculpture in a subsequent drawing or painting.

Hepworth likened her use of plaster for bronzes, which she often applied to an armature with a large flat spatula, to painting in oils. [6] It is an apt analogy since the sinuous lines of Meridian parallel the wiry urgency of a series of two-dimensional works Hepworth had also begun to make earlier in 1957, and which themselves have roots in her enthusiasm for Tachisme. As one of the art movement’s most celebrated exponents, it was therefore appropriate that Soulages saw Hepworth whilst she was in Paris to complete, what we could call, her most tachiste of sculptures (fig 5).

Fig 4

Barbara Hepworth; Torso

Oil and ink on board

1958

50.8 x 30.5 cm

Private Collection courtesy David Wade Fine Art Ltd

Photograph: Matthew Hollow Photography

© Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Fig 5

Meridian, Sculpture for State House in its original location in High Holborn, London, 1960

Hepworth Photograph Collection

© Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Whilst its influence was considerable in the 1950s, Tachisme is perhaps less-well-known here today, though that is far from true in France where the art movement originated and where Soulages is still heralded as one the country’s most important living artists. In Paris in the 1940s, a new style of abstract painting had emerged amongst a disparate group of artists associated with the École de Paris, who were linked loosely by the freely expressive ways in which they applied their paint in dabs and splotches. In 1951, the term Tachisme was first coined to describe this phenomenon; tache, from French, meaning a stain, spot, blob, blur or patch. [7] By 1955, Herbert Read noticed that the influence of Tachisme could be had spread across most of continental Europe, Britain and the USA.[8] After World War II and before art from America began to dominate, and whilst the still- fledgling British art world still looked to Paris for inspiration, it found in Tachisme an apparently intuitive, impulsive approach to art making with no dogma, manifesto or strict affiliations, which promised a fresh alternative to pre-war Constructivism and geometric abstraction.[9] For British artists, it offered an escape from the trauma of the recent past, and represented a new freedom and form of expression, without a dominant apologist or ideology, which chimed with the initial optimism of the post-war age.[10] Yet at first, there seemed to have been some confusion as to what the ‘tachist bug’ actually was and why it was important:

…I got down to Gimps [Gimpel Fils] and found they have two Soulages – one a beauty but they’ve sold it – the other nothing like so interesting. But goodness, this tachist bug – every Tom, Dick and Harry is at it with lamentable results – utterly empty. There was a Hartung though, that I found impressive… I looked at the Mathieu’s at the I.C.A. – they certainly have an authentic vitality – but, but – anyway, I’m in the devil of a muddle about it all. [11]

Margaret Gardiner was not alone in her ‘muddle’ despite looking at works by several artists who were regularly associated with Tachisme, many of whom, like Hepworth, showed with the gallery Gimpel Fils. Certainly, British critics, writers and curators (as well as collectors like Gardiner), appeared to struggle with an art movement that was both new and by its very nature, intuitive and indeterminate. At a time when debates still pitched abstraction against traditional, representational art, it is perhaps no surprise that Denys Sutton, for example, thought Tachisme seemed ‘to smack of ‘rock and roll’’.[12]Even Herbert Read, writing about Georges Mathieu for his exhibition at the I.C.A. (which Gardiner had visited), warned that such painting could be as ‘unselfconscious as a child’s scribble’.[13]To others, sceptical that the new forms of painting had no significant substance at all, Tachisme was ‘only a word’.[14]

Indeed, a number of interchangeable terms were regularly used at the time, in order to try and pin down what the elusive Tachisme might have been. Hence, art informel, abstraction lyrique, art autre, action painting and even sometimes Abstract Expressionism were used quite indiscriminately, whilst at the same time putative distinctions were being made to try and distinguish between them all. Whilst there seems to have been a certain amount of contention, this lack of definition or distinction, suggests that Tachisme also reflected something of the experimental spirit that was possible for artists to explore at that time. With French and American painters showing in post-war London, as well as British artists showing in New York and Paris, there was potential for the cross-fertilisation of developments and ideas. Tachisme, therefore, represented liberation and was just one of a growing number of artistic and philosophical choices which could be explored.

Certainly, British critics, writers and curators (as well as collectors like Gardiner), appeared to struggle with an art movement that was both new and by its very nature, intuitive and indeterminate.

From a practical perspective, Tachisme changed the act of painting. Tachisme tapped into the subconscious of the artist and as an instinctive and unmediated practice, it was not meant to require preparatory sketches or drawings, and there was no attempt to conceal the process of applying the paint. The end results looked spontaneous and gestural, and appeared to lack any traditional kind of finish. Likewise, the conventional rules regarding subject matter, representation and composition did not apply; instead, any meaning was conveyed through the effects of texture and colour. In reality, despite appearances to the contrary, a tachiste-style painting was more likely to be simultaneously aleatory and deliberate. Soulages, for example, has made preparatory sketches before committing brush to canvas. Whereas Hepworth’s paintings on prepared board, involved time-consuming preparations in advance before the more instantaneous-looking, expressive lines were later added (fig. 6). Lack of restrictions, however, meant Tachisme allowed for these apparent contradictions.

Hepworth’s numerous drawings on paper from this period, however, were made instinctively and quickly (fig. 7). They have a distinctive calligraphic appearance, for which she mainly used black ink applied by pen (or similarly hollow implement), and they share many formal and atmospheric qualities with Soulages’ paintings whose continuous, looping line, folds and bends into black ‘glyph-like structures floating in space upon a whitish ground’.[15] Soulages was known to use a decorator’s wide brush, applying pigment vertically, horizontally and diagonally, at different speeds and in different thicknesses and depths, creating an overall ‘sumptuousness of substance’.[16]

By December 1956, Hepworth situated herself within developments in contemporary painting (rather than sculpture) when she wrote to Herbert Read stating that ‘I belong to the present – apart from Ben’s [Nicholson] ptg it is Sam Francis, Soulage [sic] etc who move me most.’[17] Certainly, she would have been well aware that Soulages and a number of other artists often described as ‘tachistes’ showed with Gimpel Fils – Hepworth’s principle commercial dealer from 1956 – amongst whom included Sandra Blow, Alan Davie, Sam Francis, William Gear, Georges Mathieu and Nicolas de Staël. Soulages began working with Gimpel Fils in 1955 and had a further four shows with them in London. In 1958 and 1972 Soulages and Hepworth both had solo shows with the gallery.

Hepworth and Soulages described in later life the formative experiences which subsequently proved influential on their later, respective practices. For Soulages, a pivotal moment came when he saw a viscous tar stain on a hospital wall as he walked to school. The tar appeared at first to be in the shape of a cockerel, but the form slowly dissipated into an amorphous black morass as he approached it. This event is often proffered as an echo of Soulages own artistic odyssey from traditional oil painting to abstraction in other media, including the innovative use of tar painted onto broken glass which he started making in 1948. Soulages has also reminisced about his school-boy paintings of snow made in ink, which presaged his later, almost exclusive use of black and brown pigments. For Hepworth, a similar damascene moment occurred when she was aged seven and a teacher showed her class a slide-show of Egyptian sculpture.

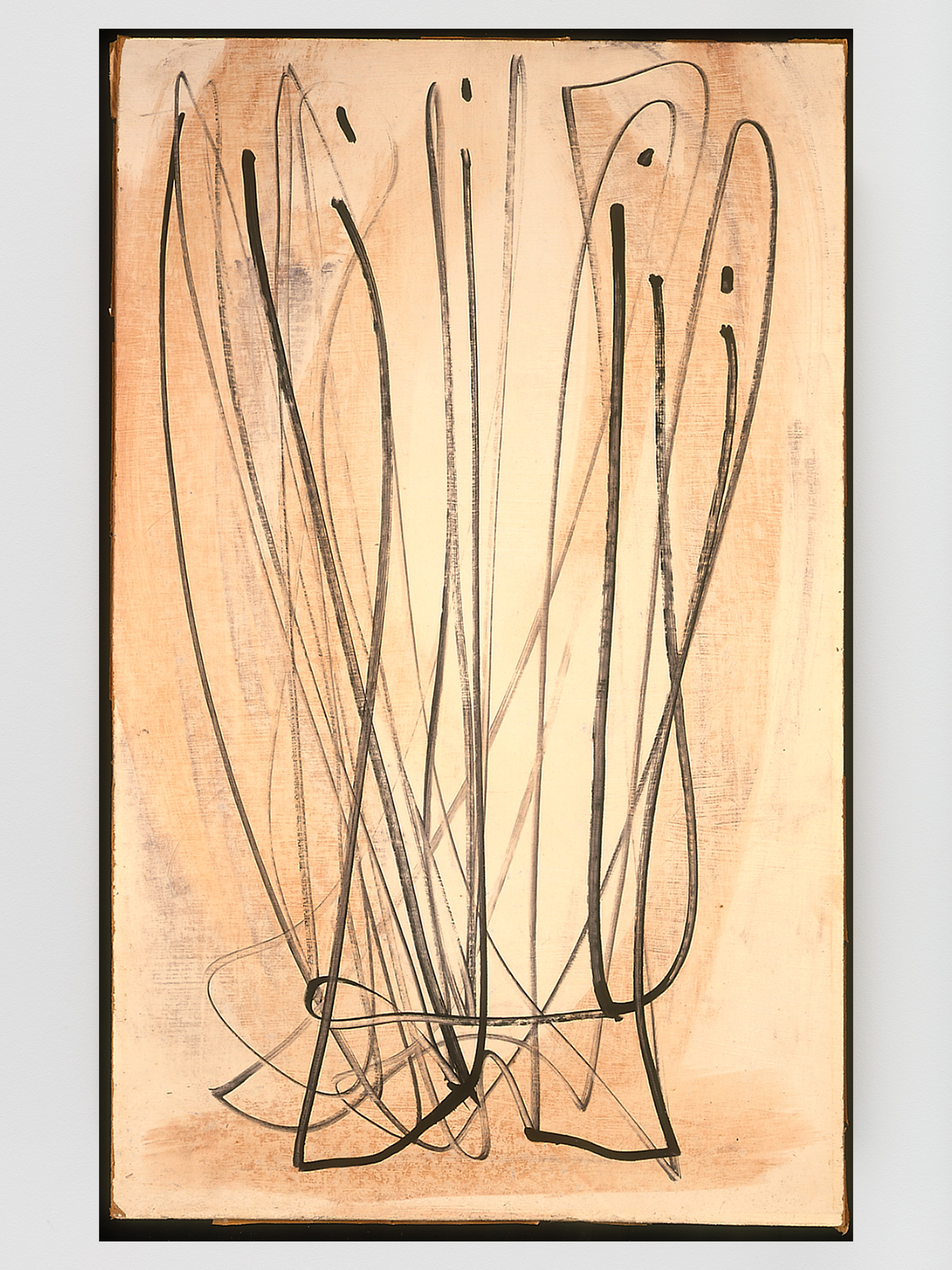

Fig 6

Barbara Hepworth

Project (Spring Morning), 1957

Oil on board

Wakefield Permanent Art Collection (Hepworth Wakefield)

© Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Fig 7

Barbara Hepworth

The Seed (Project for Metal Sculpture), 1957

Ink on paper

Wakefield Permanent Art Collection (Hepworth Wakefield)

© Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Whilst the journeys she recalled taking with her father, as he drove across West Yorkshire, formed a fundamental connection between her, her imagination and the landscape, where the countryside and the human position within it, were seen in purely sculptural terms. Soulages also grew up surrounded by an untamed countryside. As a child he knew from first-hand experience the Neolithic menhirs and dolmens which populated the countryside surrounding Rodez, as well as those within the city’s collections at the Musée Fenaille; the importance of similar indigenous standing stones had been ‘discovered’ by Hepworth and her Modernist peers in the 1930s.

Hepworth revealed a remarkable propensity for innovation and reinvention during her career, far more than she is often credited with. Yet of the two artists, Soulages probably had the experimental edge as far as his use of non-art materials was concerned, perhaps most famously the brous de noix he began using on paper in the mid-1940s and which he has continually returned to throughout his on-going career. Both had been drawn, perhaps inevitably, to Paris. Hepworth visited there on a number of occasions whilst she was still studying at the Royal College of Art in the 1920s. Latterly she also went with Ben Nicholson in the 1930s when the couple expanded greatly the scope of their artistic network with artists then based in France, many of whom – including Braque, Calder, Gabo and Mondrian – became close friends.

The younger Soulages moved to Paris from Rodez to study at the École nationale superieure des beaux-arts in 1939, but he left when war was declared to serve in the army. Following capitulation and during the German occupation of France, Soulages avoided working with the Service de Travail Obligatoire and survived as an itinerant farm labourer during which time he did not paint at all. [18]

A pivotal moment came in 1942 when Soulages saw a Mondrian painting, reproduced in black and white, illustrating an article on degenerate art in the Nazi propaganda magazine Signal. The rigorous geometry of a Mondrian was perhaps a surprising source of inspiration for Soulages, but in fact he was drawn to how the ‘simple structures of planes and classified organisation of forms could operate pictorially’.[19] The visual memory was stored and saved for later use, suggesting that there is more order and control in Soulages’ paintings than it seems at first glance.

Hepworth and Mondrian had shown together in the exhibition Abstract and Concrete in 1936, having met the year before, and established a close friendship; when Mondrian moved to London in 1938, they were at the very centre of a vibrant community of international contemporary artists until it was dispersed by the advent of World War II. Mondrian initially stayed on, only deciding to leave for New York when France surrendered.[20] By then Hepworth, Nicholson and their children were already in Cornwall, having been visiting friends when war was declared; for Hepworth, the holiday to St. Ives became a permanent residence. Whilst the realities of the war also impacted on her ability to work, Hepworth was still able to draw and make some plaster sculptures, moreover the older artist had been able to establish a significant career before the war and even exhibited during it (notably, she had her first retrospective exhibition at Temple Newsam in 1943).

Soulages returned to Paris in 1946, and after the caesura of the war years was quick to make great strides. Although his work was rejected by the jury of the Salon d’Automne in 1946 (whereas Hepworth’s work had been included in 1938)

Soulages’ paintings made a considerable impact in October 1947 at the Salon des surindépendants; amongst some two-thousand artworks

Soulages’ paintings made a considerable impact in October 1947 at the Salon des surindépendants; amongst some two-thousand artworks, his paintings were ‘marked by the absence of a recognizable subject or even a suggestive title, by sombre tonalities and black contours in comparison to the numerous brightly coloured, post-fauvist and moderately cubist canvases’.[21] In 1948 he showed at the Salon des Réalités nouvelles, along with other loosely-grouped ‘lyrical’ abstractionists and indeed Barbara Hepworth; as Dr Sophie Bowness has noted, Hepworth exhibited at three Salons organised by the arts society from 1947-49 and again in 1957, having been included in its pre-war incarnation in 1939.[22] Sonia Delaunay, Arp and Pevsner were members of its organising committee after the war. Hence, not only had work by Hepworth and Soulages been seen in the same exhibition, but their social and professional circles had begun to overlap.

Hepworth owned a number of art works by fellow contemporary artists (as well as some historic artefacts), including an etching by Soulages entitled Eau-forte XIV, 1961 (fig. 8), which is now in the collection of the Hepworth Wakefield; although it is not yet clear from records whether she obtained it from Gimpel Fils, if it was a purchase or if it was a gift. It is furthermore interesting to note that both she and Soulages agreed to put their names to the anti-Vietnam War statement organised by Margaret Gardiner, and which was placed in the New York Times on 12 December 1965.[23] Hepworth also kept in her personal library, the catalogue from the shows Soulages had with Gimpel Fils in 1967.[24] It therefore seems a fair assessment that Hepworth sustained the friendship with Soulages and retained a certain regard for Tachisme over an extended period of time. Tachisme was therefore less the passing ‘bug’ which Margaret Gardiner had referred to, but something that Hepworth felt very deeply and personally. Indeed, as she stated in 1958, ‘of all the ‘pulses’ of creation’ Tachisme had moved her ‘more profoundly than any other.' [25]

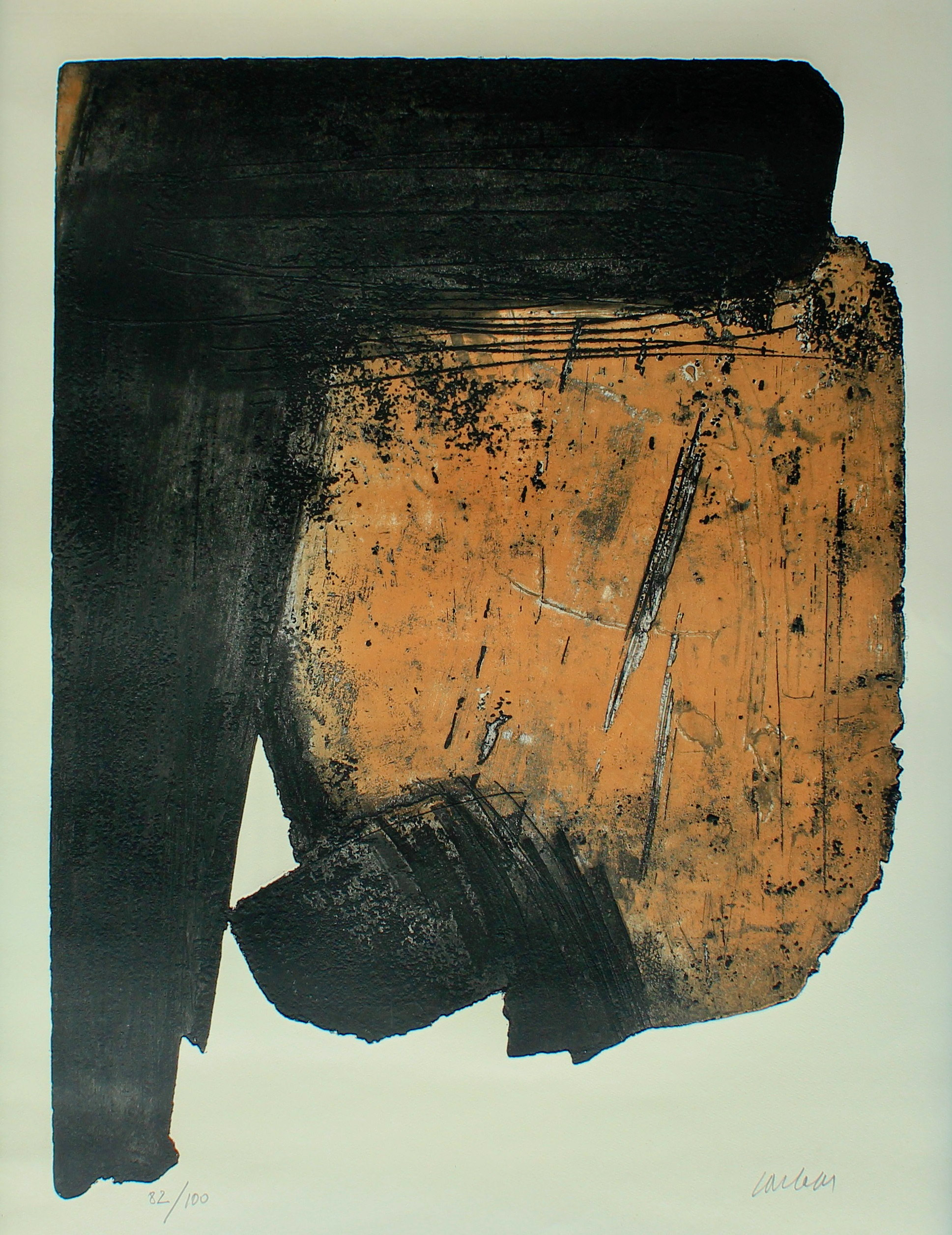

Fig 8

Pierre Soulages,

Eau-Forte XIV, 1961

Etching on Arches paper, signed in pencil and numbered 82/100

Printed by Lacourière, Paris

Wakefield Permanent Art Collection (Hepworth Wakefield)

Stephen Feeke is an independent writer and curator, and is currently researching a PhD on Barbara Hepworth’s early bronzes (Courtauld Institute of Art). Stephen is a member of the Hepworth Research Network at the Hepworth Wakefield and is contributing to the catalogue accompanying the first Hepworth exhibition at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (summer 2022). He was previously a Director at the New Art Centre, Roche Court, where he worked closely with the Hepworth Estate

References

[1] Letter to Herbert Read, 1 December 1959, Herbert Read Archive, University of Victoria, British Columbia, Special Collections,HR/BH 225-26. Subsequent letters from Hepworth to Read are from the same source.

[2] The guest list is in the Gimpel Fils archives; see Sophie Bowness, ‘Barbara Hepworth et Paris’, Barbara Hepworth, exh. cat. Paris: Musée Rodin and Fine éditions d’art, 2019, p. 37. Sadly, records do not confirm whether Soulages actually attended.

[3] State House was demolished in 1990. Meridian had been removed on 22 June 1989, prior to being sold it was treated at Robert Harris Conservation and a bronze base was cast at A&A Foundry. On 31 October 1989 the sale was agreed between the dealer Patricia Wengraf and Donald Kendall of PepsiCo, and the sculpture was subsequently sited in the grounds of the PepsiCo headquarters in Purchase, New York State (what are now called the Donald M. Kendall Sculpture Gardens).

[4] Hepworth described Meridian in her conversations with Alan Bowness published in Alan Bowness, ed.), The Complete Sculpture of Barbara Hepworth 1960-69, London: Lund Humphries, 1971, p.10.

[5] See the summary in Sophie Bowness, (ed.), Barbara Hepworth: The Plasters: The Gift to Wakefield, London: Lund Humphries, 2011, pp. 64-71

[6] Hepworth’s analogy to painting with oils is used generically to describe her process of using plaster on armatures: ‘as in Curved Form (Trevalgan)’, see ‘The Sculptor Speaks’, recorded talk for the British Council, 8 December 1961, transcript reproduced in Sophie Bowness, (ed.), Barbara Hepworth: Writings and Conversations, London: Tate Publishing, 2015, pp. 158-59.

[7] Pierre Guéguen first used the term in 1951 at a conference before it appeared in the article ‘Le Bonimenteur de l’Academie Tachiste’, Art d’Aujourd’hui, série 4, no. 7, Oct-Nov 1953, pp. 52-53. See Fiona M. Gaskin, Aspects of British Tachisme 1946-5, M.A. diss., Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 1996, p. 2. The term was given wider currency by the French critic Michel Tapié in his book Un art autre, Paris: Gabriel-Giraud et fils, 1952 and the accompanying exhibition (which included works by Soulages as well as Rothko and Sutherland).

[8] Herbert Read, ‘Art: A Blot on the Scutcheon’, pp. 54-57, in Stephen Spender and Irving Kristel, (eds.), Encounter, vol. V, No. 1, July 1955, p. 54.

[9] The activities of Circle and Unit One (in which Hepworth had played major roles) sought to formalise artists into groups, though such attempts at affiliation were often short lived. See: Charles Harrison, English Art and Modernism: 1900-1939, New Haven and London: Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 1981, reprint 1994, p.213.

[10] Fiona M. Gaskin, ‘British Tachisme in the Post-War Period 1946-57’, in Margaret Garlake, (ed.), Artists and Patrons in Post-War Britain: Essays by postgraduate students at the Courtauld Institute of Art, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Ltd., 2001, p. 21.

[11] Letter from Margaret Gardiner to Barbara Hepworth, (dated July 1956 by Alan Bowness), Tate Gallery Archives, TGA 20132/1/65/16

[12] Denys Sutton, ‘Preface’, Metavisual, Tachiste, Abstract: Painting in England To-Day, exh. cat. London: Redfern Gallery, 1957, n.p.

[13] Herbert Read, ‘Mathieu’, Georges Mathieu, exh. cat., London: Institute of Contemporary Art, 1956, n.p. Hepworth and Read actually took children’s art very seriously.

[14] René Drouin defined it as a ‘splotch’ which suggests something uncontrolled or accidental. See: ‘Tachisme is only a word’, Architectural Design, 26:8, 1956, p. 7.

[15] Natalie Adamson, ‘Vestiges of the Future: Temporality in the Early Work of Pierre Soulages’

Art History, no. 1, February 2012, p. 144.

[16] James Fitzsimmons, ‘Art and Architecture’, May 1956, reproduced in Pierre Soulages, exh. cat., Gimpel & Hanover Galerie, Zurich, January-February 1967, and Gimpel Fils Gallery, London, March-April 1967, n.p.

[17] Letter to Herbert Read, HR / BH 169, 15 December 1956.

[18] With thanks to René Gimpel for his note regarding the Service Travail Obligatoire.

[19] Natalie Adamson, 2012, op. cit., p. 133.

[20] Sophie Bowness, ‘Mondrian and London’, in Christopher Green and Barnaby Wright, (eds.), Mondrian: Nicholson: In Parallel, exh. cat., London: Courtauld Gallery and Paul Holberton, 2012, p. 59.

[21] Natalie Adamson, 2012, op. cit., p. 126.

[22] Sophie Bowness, 2019, op. cit., p. 37.

[23] Margaret Gardiner Papers, vol. I (ff. 163), correspondence and papers; 1962-1965, West European artists' protest on Vietnam, 1965, Add MS 71603, 83-163, British Library.

[24] The catalogue accompanied Soulages’ shows with Gimpel Hanover Galerie, Zurich and Gimpel Fils, London, in 1967. As part of Hepworth’s personal library, it is held by the Tate Archive (TGA 20196/1/338).

[25] Letter to Herbert Read, Wednesday 1958 (no month), HR / BH 201.