The Art Bronze Foundry was established in 1922 in Fulham Road, Chelsea by its founder Charles Gaskin (1890-1969). For over ninety years it catered for some of the most eminent British sculptors including Barbara Hepworth, Henry Moore, Jacob Epstein, Elizabeth Frink and Anthony Caro, while always remaining first and foremost a family business passed down over three generations. This article explores Barbara Hepworth’s (1903-75) relationship with the Art Bronze Foundry, a relatively under-researched aspect of her work. While Hepworth’s relationships with her gallerists have been discussed in some depth, less attention has so far been devoted to her work with her four foundries (the Art Bronze Foundry, Holman’s of St Just, Susse Frères, Paris and the Morris Singer Foundry), with the exception of Morris Singer. As Dr Sophie Bowness, art historian and custodian of the Hepworth Estate has noted, ‘Hepworth’s collaborative relationships with her foundries were of vital importance to the production of her bronzes’. Arguably then, an examination of Hepworth’s working relationship with the Art Bronze Foundry, the first foundry she used after transitioning to working in bronze in 1956, offers the potential to provide new insights into her early works in bronze casting.

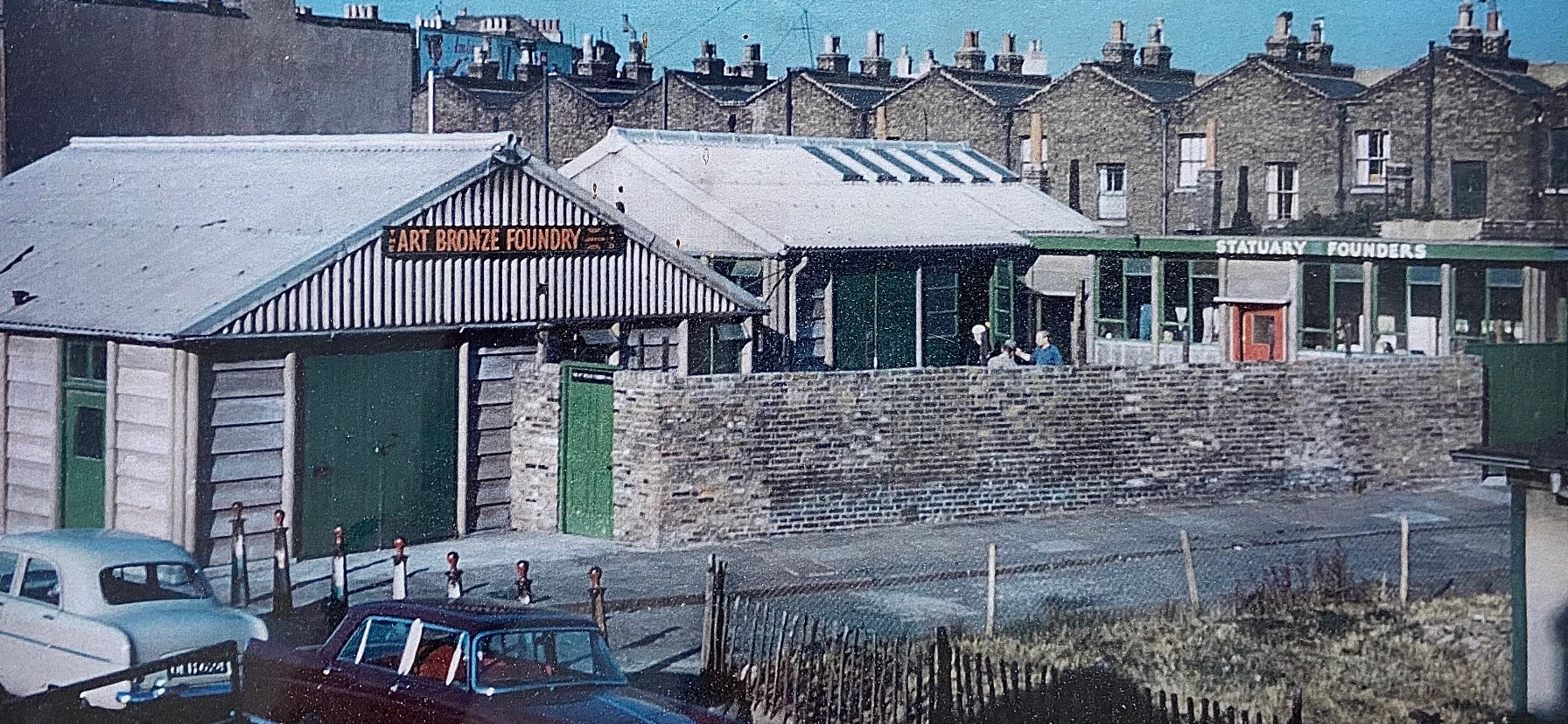

The Art Bronze Foundry was one of a number of new foundries established after the First World War to meet the demand for the erection of war memorials. Its founder Gaskin had previously worked at Parlanti’s foundry prior to the war, one of several Italian foundries which had set up premises in London around the turn of the century and specialised in the lost wax casting technique. Lost wax casting involves producing a wax version of a sculpture which is encased in another mould that can withstand high temperatures. The wax is then melted to leave a cavity into which molten bronze is poured. The Art Bronze Foundry – or ‘Gaskin’s’ as it was known informally – similarly became known for working exclusively in the lost wax process. By the 1940s the Foundry counted both Epstein and Moore as regular clients, with the latter continuing to send work for much of his life. But it was the 1950s that was the real heyday for the Art Bronze Foundry, when it moved premises to a purpose-built facility off the Kings Road and took on work for sculptors including Caro, Frink, Lynn Chadwick, F.E. McWilliam and Eduardo Paolozzi. [FIG 1] Doubtless it was this growing reputation which encouraged Hepworth to approach the Foundry when she began working in bronze in 1956.

The Art Bronze Foundry was one of a number of new foundries established after the First World War to meet the demand for the erection of war memorials.

Fig. 1

The Art Bronze Foundry, Michael Road, London.

Courtesy of the Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

Fig. 2

Ascending Form (Gloria) 1958 at the Art Bronze Foundry, 1996. Courtesy of the Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

Hepworth sent her first bronze Curved Form (Trevalgan) 1956 to be cast at the Art Bronze Foundry, as well as several other works produced in 1956, including Involute II and Helius. However, her correspondence with the Foundry (held by the Art Bronze Foundry Archive and Tate Archive) only dates from 1958, meaning that it is difficult to glean insights into her early working relationship with Gaskin and his staff. There are similarly few references to the Art Bronze Foundry in any of the major correspondence series’ in Hepworth’s personal papers. A letter to her dealer Gimpel Fils dated 1957 is more revealing, however. Writing to Kay Gimpel, gallery manager and wife of Charles Gimpel, Hepworth asked: ‘please try to sell something for me as I owe the Bronze Foundry about £700!’ Receipts from the Art Bronze Foundry indicate that Hepworth’s individual bronze casts generally cost between £30 and £200, suggesting that they had already produced multiple casts for her by this point. Only two letters between Hepworth and the Art Bronze Foundry survive from the 1950s, but there is regular correspondence from 1960 to 1971 – the final year in which the Foundry produced a new cast for her – from which it is

possible to build up a picture of their ongoing relationship. Records compiled by the late Michael Gaskin, son of Charles Gaskin, indicate that in total the Art Bronze Foundry cast approximately a hundred bronzes for the artist. Indeed, in 1971 the Foundry observed that it would be ‘strange here with none of your work on the “floor”’. While Hepworth sent her last new plaster to the Art Bronze Foundry in 1963, they continued to produce casts for her until 1971. Very often it would take several years to complete an edition of a work. For example, although the first cast of Ascending Form (Gloria) 1958 was produced in 1960, the final artist’s copy was only cast in 1971. Although Hepworth never sent any new work to the Art Bronze Foundry after 1963, letters as late as 1966 indicate that she was planning to produce new work for casting. Following her death, the Foundry continued to provide occasional remedial work on casts, such as repairing a crack to a cast of Ascending Form in 1996. However, no posthumous casting has been undertaken as per the explicit request of the artist. [FIG 2]

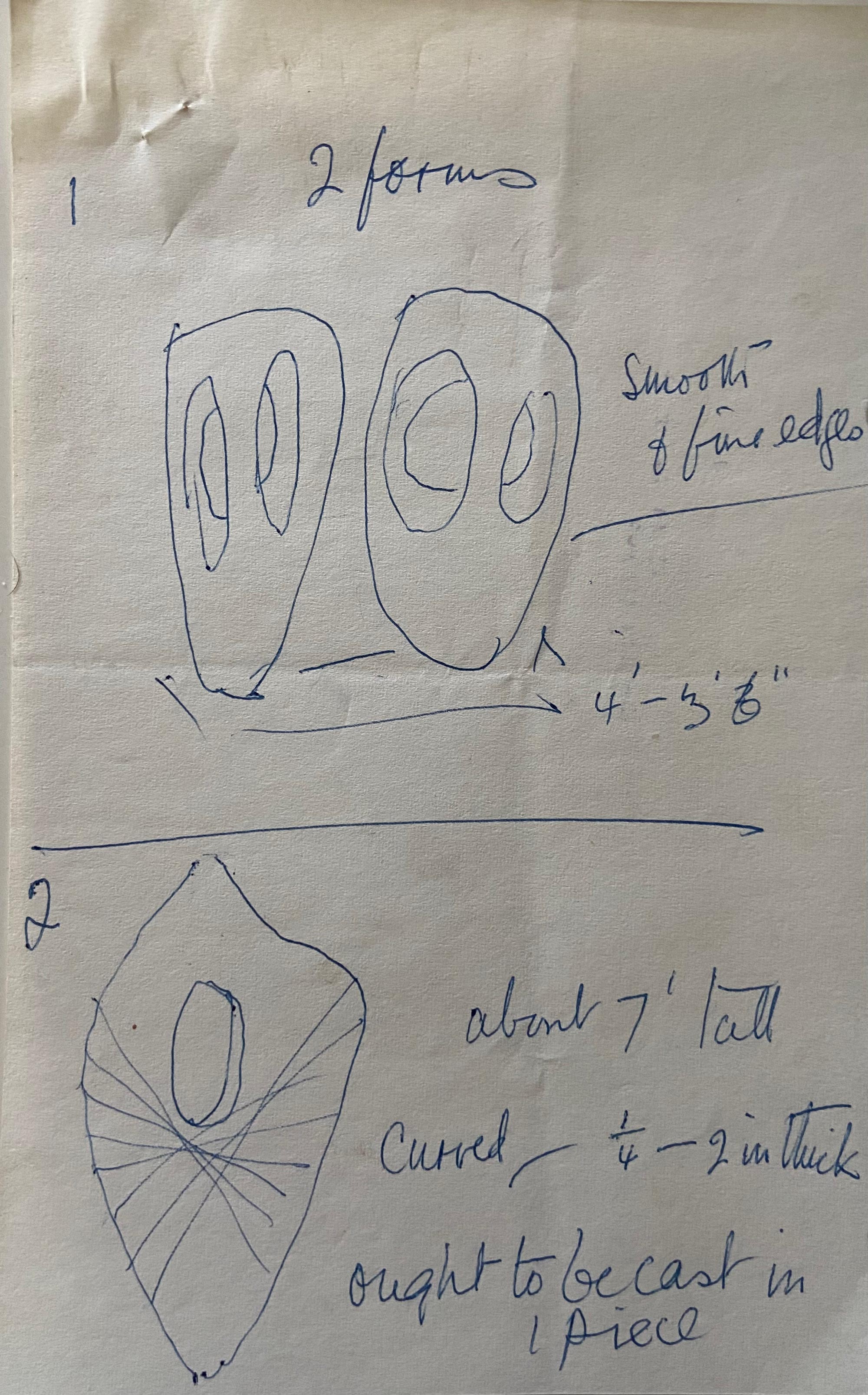

Fig. 3

Barbara Hepworth, Drawings of Two Forms in Echelon 1961 and Curved Form (Bryher II) 1961.

Courtesy of the Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

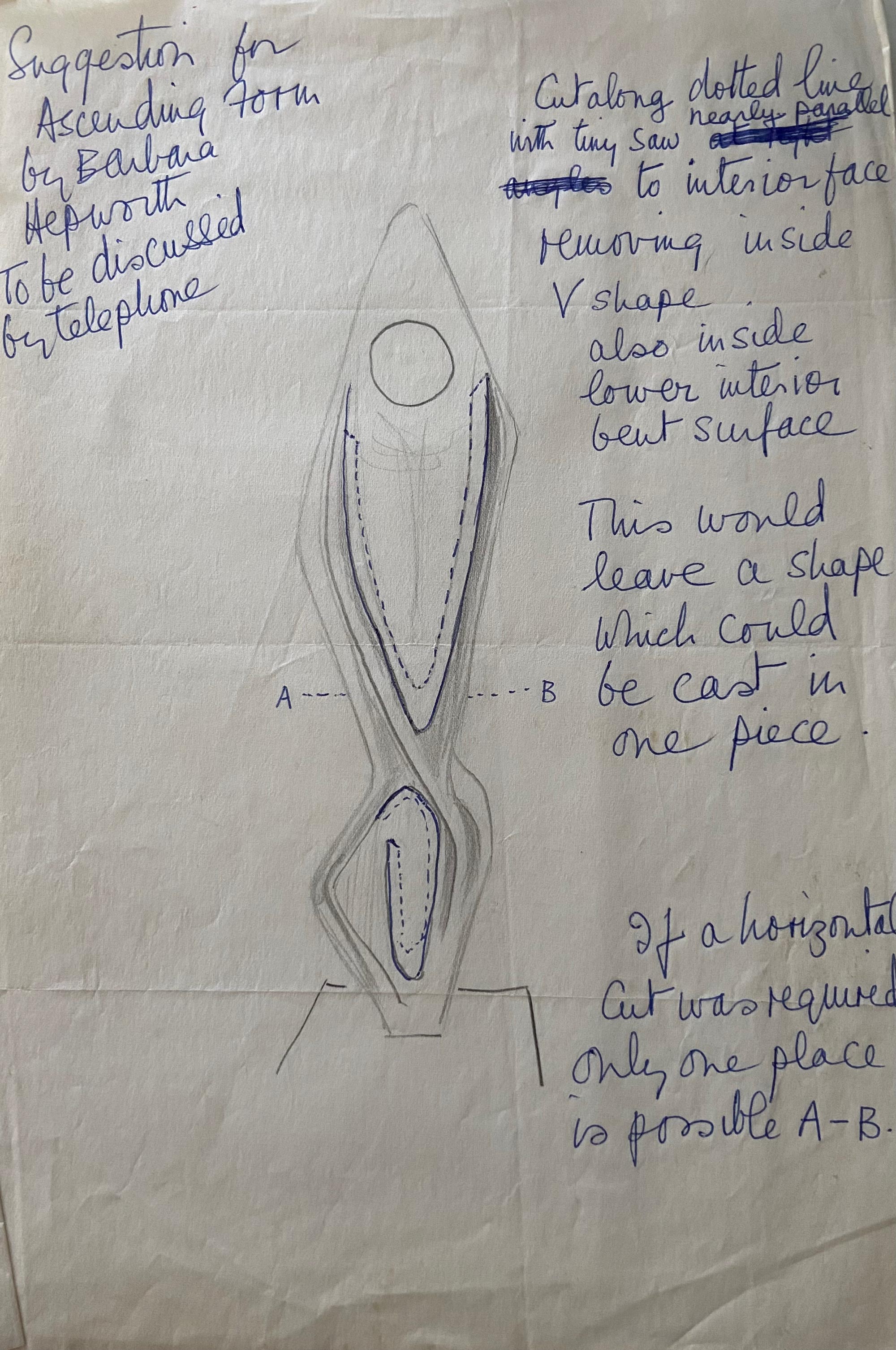

Fig. 4

Barbara Hepworth, Drawing of Ascending Form (Gloria) 1958.

Courtesy of the Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

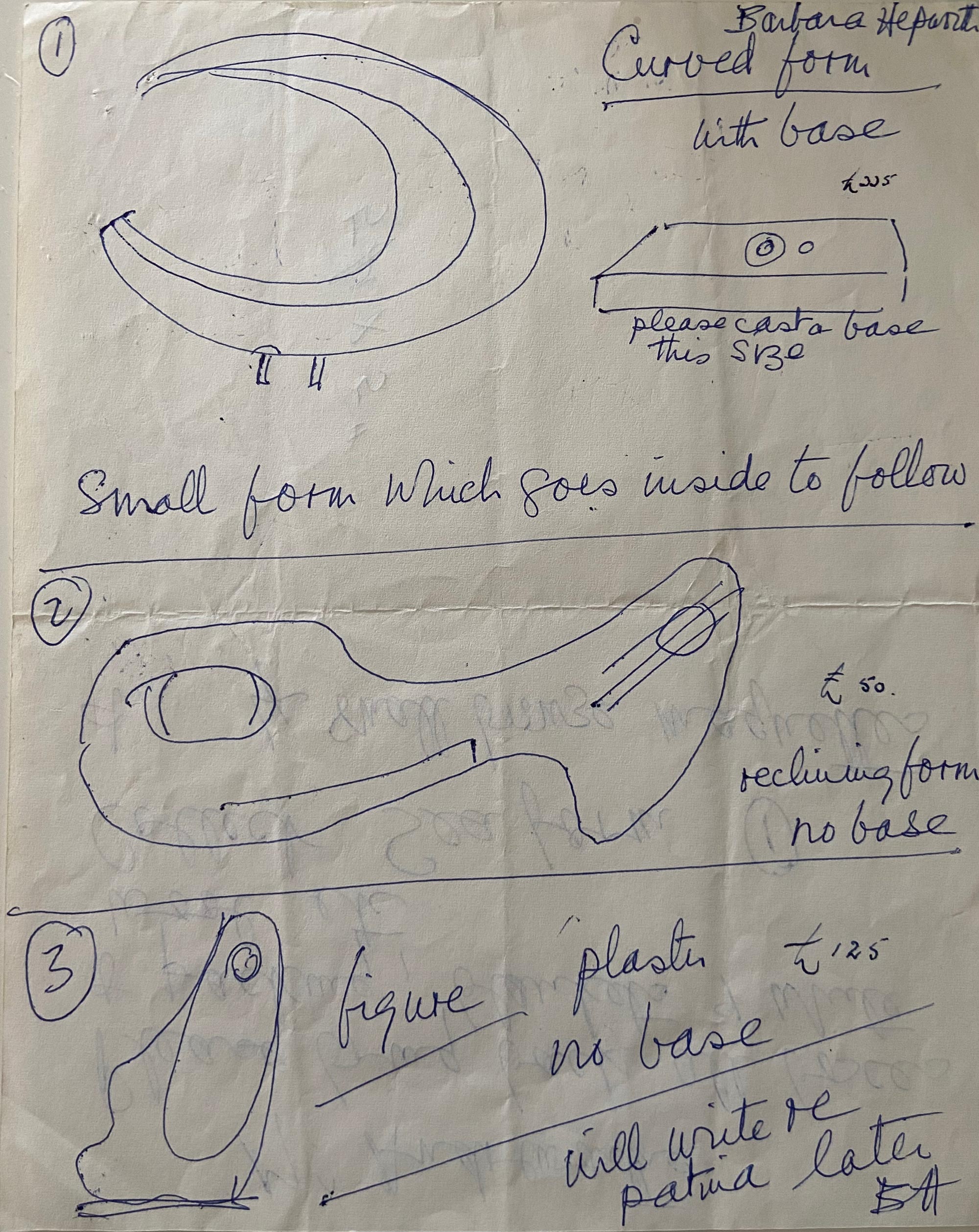

Fig. 5

Barbara Hepworth, Drawings of Curved Form with Inner Form (Anima) 1959, Reclining Figure (Trewyn) 1959 and Coré 1955-6/1960.

Courtesy of the Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

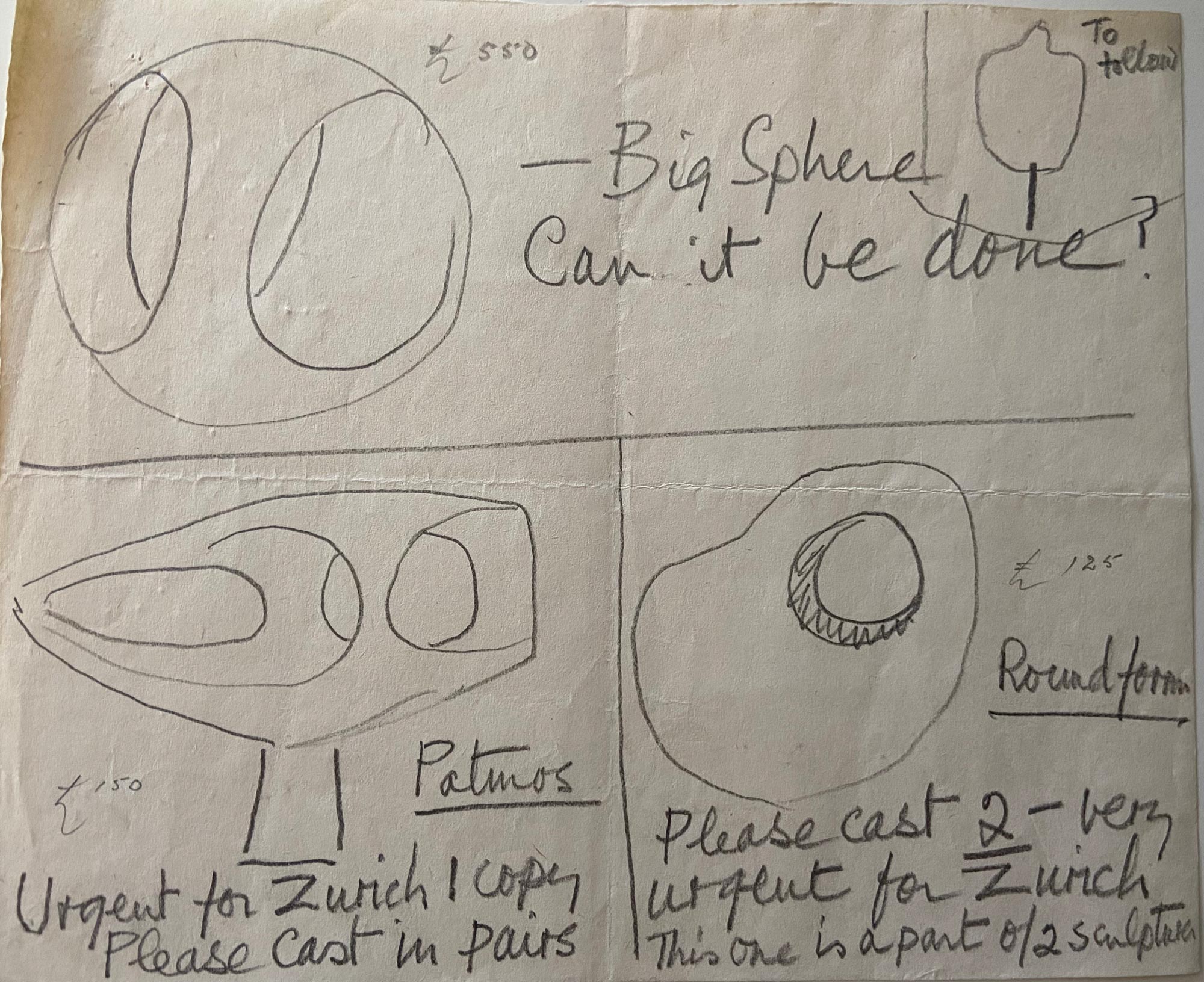

Fig. 6

Barbara Hepworth, Drawings of Sphere with Inner Form 1963 and Bronze Form (Patmos) 1962-3.

Courtesy of the Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

Hepworth’s correspondence with the Art Bronze Foundry provides important insights into her bronzes of the late 1950s and early 1960s. The majority of works that the Foundry cast for her are small- to mid-size; the largest work mentioned in the correspondence is Curved Form (Bryher II) 1961 which is seven foot tall. [FIG 3] The Art Bronze Foundry worked exclusively in the lost wax technique, which is generally reserved for more complex and detailed surfaces, while sand casting is used to cast larger works and simpler forms. For works that required sand casting, such as Curved Form (Trevalgan), the Foundry would sub-contract to Taylor’s Foundry in Middlesex. For her larger public commissions, Hepworth worked with either the Paris foundry Susse Frères or the Morris Singer Foundry, the latter of whom became her principle foundry after 1963 where she sent all new work to be cast. Meridian 1958-60, her first monumental bronze for the State House in High Holborn, London, was cast by Susse Frères. Later commissions including Winged Figure 1961-3 for John Lewis on Oxford Street, London and Single Form 1961-4 for the United Nations in New York were all cast by Morris Singer, who were highly regarded for casting large-scale work. Hepworth’s letters, the majority of which were directed to Gaskin himself, contain detailed technical instructions, ideas for patinas and even sketches for individual, recognisable works. These include Ascending Form (Gloria) 1958, Curved Form with Inner Form (Anima) 1959, Coré 1955-6/1960, Two Forms in Echelon 1961, Bronze Form (Patmos) 1962-3 and Sphere with Inner Form 1963 [FIG 4-6]. While she rarely produced maquettes or drawings for sculptures, she would make working sketches to show her assistants or foundries what she wanted to achieve.

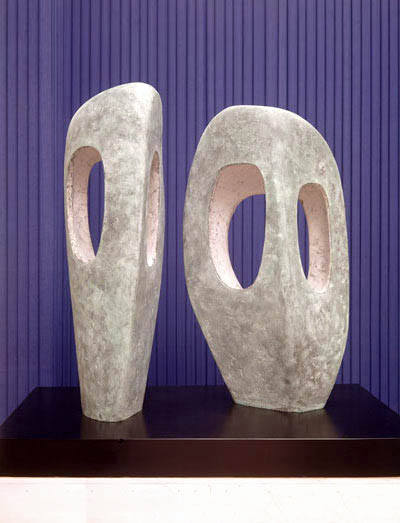

Occasionally a foundry might also request to see a model, as the Art Bronze Foundry did for Curved Form (Bryher II), although there are no known instances of her actually providing such models. The correspondence offers an important insight into Hepworth’s initial vision for individual works as well as their subsequent development. For example, she seems to have originally intended Two Forms in Echelon to be a stringed work, an unusual example of her changing direction in the evolution of a work. [FIG 7] Writing to Charles Gaskin in 1961, she stated, ‘I intend to put strings in these bronze forms when cast and a high degree of accuracy and precision is required.’ In a later letter she added, ‘the edges of the holes through the middle need to be solid to ½ inch back so that I can drill exactly for the strings which I have to put in myself in both the forms.’ It was common for Hepworth to request Gaskin to leave a work unstrung to complete herself. Nonetheless, she seems to have been interested in potentially asking the Art Bronze Foundry to undertake stringing work on her behalf, observing that ‘my assistants tell me that you have workmen who are able to do fine stringing. When I am next in town, I should like to come and see you about this, and casting in gold.’ That Hepworth originally intended to string the sculpture is perhaps not surprising given that she produced another strung Forms in Echelon work the same year, her Maquette, Three Forms in Echelon 1961, which formed her initial proposal for the John Lewis commission. Two Forms in Echelon also looked back to her earlier 1938 carving Forms in Echelon, which similarly focused on the space and relationship between two upright forms, and is one of several works produced in the 1960s which revisited the forms that she had been exploring in the 1930s.

The Art Bronze Foundry worked exclusively in the lost wax technique, which is generally reserved for more complex and detailed surfaces, while sand casting is used to cast larger works and simpler forms.

Fig. 7

Barbara Hepworth, Two Forms in Echelon 1961, plaster, with shellac and brown paint, 120 x 43 x 28 cm and 112 x 63 x 30 cm, prototype for casting in bronze. Wakefield Permanent Art Collection (The Hepworth Wakefield).

Presented by the artist’s daughters, Rachel Kidd and Sarah Bowness, through the Trustees of the Barbara Hepworth Estate and the Art Fund, 2011.

Barbara Hepworth © Bowness. Photograph: Mark Heathcote

Fig. 8

Barbara Hepworth, Two Forms in Echelon 1961, bronze. Photographed at Hepworth’s 1962 retrospective at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London.

The Hepworth Photograph Collection.

Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

The correspondence also provides valuable insight into Hepworth’s intentions regarding the colouring of her bronzes. This information has a practical application, providing important evidence for conservators today when repatinating bronzes. Hepworth had experimented with incorporating colour into her sculptures since the late 1930s when she first began to paint the interiors of her plaster Sculpture with Colour works, emphasising the contrast between interior and exterior form. This continued in the 1940s with carvings such as Pelagos 1946 and Wave 1943-4, where the hollowed out wooden cavities were painted pale blue. It was therefore only natural that colour would take on an important role in her move to bronze casting in the 1950s. Hepworth not only provided detailed written instructions to foundries about her preferred patination colours, but also sent them plasters which were painted. Sometimes this was to provide an indication of the patina desired; on other occasions it seems to have had a more practical purpose to ensure that any accidental damage would show up. In several instances this has led to a level of discrepancy between the colour of the painted plaster and the patinated bronze. The colour wash applied to the plaster of Two Forms in Echelon to show up damage in transportation bears little resemblance to Hepworth’s written instructions to Gaskin which stated that the patina should be ‘very thin on the outside, i.e. just a hint of green with edges of texture showing bronze colour through. The interior I would like white[…]’. [FIG 8] Patinas could also vary within an edition, sometimes intentionally, and at other times due to the difficulty of repeating the exact same colour on different casts.

For example, in 1964 Hepworth described herself as ‘stressed’ by the change in colour between editions 2/7 and 3/7 of Bronze Form (Patmos), requesting Gaskin ‘make 3/7 conform with 2/7 with the green tinge carried throughout […] the whole project looks much better as a kind of “rock covered with lichen”’. The ‘pure bronze effect’ that the Art Bronze Foundry had obtained for cast 3/7 instead seems to be closer to the bronze colour of the painted plaster. [FIG 9] Hepworth’s intended to repatinate cast 3/7: ‘can you tell me what you used to render 3/7 a pure bronze colour? Before I can rework this patina I really must know whether I have to remove surface oil or whatever?’ It was not unusual for Hepworth to work on the patination of bronzes herself; as with cast 3/7 of Bronze Form (Patmos), she would rework the patina of any casts which did not meet her satisfaction. On occasion, she might even request for casts to be sent to her unpatinated, presumably so she could experiment with the patina to obtain the right colour. She requested Gaskin to send the first cast of Single Form (Chûn Quoit) to her unpatinated, adding that ‘if it is like your last casts it will be most excellent’. She seems to have been particularly pleased with the patinas that the Art Bronze Foundry obtained on the later casts of this work, writing to Gaskin the following year that ‘the patina of 4/7 was the best you have done, I like it tremendously. Could you do Nos. 5 & 6 in the same way and I would very much appreciate it if you could write and tell me how to produce this same patina on one of the earlier copies I have here which is not half so lively.’ [FIG 10]

Fig. 9

Barbara Hepworth, Bronze Form (Patmos) 1962–3, plaster, lacquered and painted brown, 65 x 97.5 x 34.5 cm, prototype for casting in bronze. Wakefield Permanent Art Collection (The Hepworth Wakefield).

Presented by the artist’s daughters, Rachel Kidd and Sarah Bowness, through the Trustees of the Barbara Hepworth Estate and the Art Fund, 2011.

Barbara Hepworth © Bowness. Photograph: Mark Heathcote

Fig. 10

Barbara Hepworth, Single Form (Chûn Quoit) 1961, bronze, 113 x 68 x 43 cm, Hepworth Estate.

Barbara Hepworth © Bowness. Photograph: Jerry Hardman-Jones

Although Hepworth seems to have primarily favoured green and blue patinas – as in those of Two Forms in Echelon and Bronze Form (Patmos) – she did also request the use of white patinas on occasion. Sometimes this would be applied to the interior of a sculpture to provide a contrast between interior and exterior, as in Two Forms in Echelon where she specified that the interior should be ‘white as you did in “curved form with inner form”.’ However, for Cantate Domino and Ascending Form (Gloria) (both 1958) she requested that the whole sculptures be patinated white. The presence of white colouring can be seen in archival photographs taken by Brian Butt of Studio St Ives photography. [FIG 11] As sculpture conservator Jackie Heuman notes, ‘this was an unusual colour for bronzes for the time and the foundry would probably have had to experiment to find a way to produce a stable white patina.’ Although the Art Bronze Foundry would occasionally receive requests for a white patina, including for a horse and rider sculpture by Elizabeth Frink, it was not something that they would regularly produce. The white colouring was achieved through the application of bismuth nitrate dissolved in water to make a solution, which when applied to a bronze that had been heated with a blowtorch, would create a white oxidisation. White patinas could also be produced by using white paint and the white residue left on casts from the investment material (the mould for casting bronzes). Sometimes even milk and lime were used. Indeed, the patina for Ascending Form is referred to in correspondence as ‘Milk White’. When assessing the cast of Ascending Form in Alnwick Gardens, Northumberland (on long loan from the Arts Council Collection), sculpture conservator Laura Davies identified white residue on the surface of the bronze. Scientific analysis carried out by x-ray diffraction on the residue by Richard Sweeney, Senior Research Facility Manager at Imperial College, London revealed the presence of calcite, rutile and dolomite, consistent with 1960s and 1970s household paint preparations rather than with a traditional chemical patina. There is now a desire to undertake further analysis to examine the organic components of the residue.

Hepworth’s desire for a white patina is of both material and symbolic significance. Jackie Heuman suggests that ‘perhaps, like Giacometti, she wanted the bronze to reflect the matt white light of plaster she had grown so accustomed to seeing’. Among the correspondence in the Art Bronze Foundry Archive is a photograph of the plaster prototype of Cantate Domino taken by Studio St Ives in the garden of Hepworth’s Trewyn Studio. [FIG 12] Ascending Form (Gloria) and Cantate Domino are also two of her mostly overtly religious works, thereby adding a level of spiritual symbolism to the use of the white patina. Both works reference sacred vocal music, which Hepworth was exploring during this period as part of a wider interest in Early English music, encouraged by her friend, the South African composer Priaulx Rainier. ‘Cantate Domino’ refers to the opening line of Psalm 98, ‘O Sing unto the Lord’, and has been set to music by composers including the Italian Renaissance composer Claudio Montiverdi. ‘Gloria’, or ‘Gloria in Excelsis Deo’ in full, translates as ‘Glory to God in the highest’ and occurs in the Roman Mass and Communion Service. Famous settings include those by Baroque composers George Frederick Handel and Antonio Vivaldi.

Both Ascending Form (Gloria) and Cantate Domino utilise a rising diamond form, described by the critic Edwin Mullins as ‘a free stylisation of the human hand raised in supplication and praise’. The implied spiritual significance is made explicit through photographs taken by Studio St Ives. Cantate Domino appears framed against St Ives Parish Church [FIG 13], while Ascending Form is shown dappled with sunlight, seeming to literally ‘ascend’ heavenwards [FIG 14]. Hepworth had hoped for Cantate Domino to be used as a headstone for her grave but it was denied on account of the sculpture being too tall. Instead, a cast of Ascending Form is located in the entrance to Longstone Cemetery, Carbis Bay, where the artist is buried.

Fig. 11

Ascending Form (Gloria) 1958 in the garden of Trewyn Studio, St Ives, May 1960. Photograph by Studio St Ives/ Butt 810.

The Hepworth Photograph Collection © Bowness

Fig. 12

Plaster for Cantate Domino 1958 in the garden of Trewyn Studio, May 1958. Photograph by Studio St Ives/ Butt 630.

The Hepworth Photograph Collection © Bowness

Fig. 13

Cantate Domino 1958 in the garden of Trewyn Studio with St Ives Parish Church in the background, September 1958. Photograph by Studio St Ives/ Butt 638.

The Hepworth Photograph Collection © Bowness

Fig. 14

Ascending Form (Gloria) 1958 in Trewyn Studio, January 1959. Photograph by Studio St Ives/ Butt 680.

The Hepworth Photograph Collection © Bowness

In June 1971 Michael Gaskin wrote to Hepworth to inform her that the final cast 0/6 of Ascending Form had been completed. In September of the same year, Roy Francis provided Hepworth with the certificate of destruction for the plaster at her request. Francis, along with Michael Gaskin, Len Freiensener and Bill Hayter had taken over as directors of the Art Bronze Foundry following Charles Gaskin’s death in 1969. This was the last new bronze that the Foundry would produce for Hepworth, although later that year they repatinated a further cast of Ascending Form which had recently returned from her 1970 exhibition at the Hakone Open-Air Museum in Japan, where it had acquired a ‘black atmospheric crust’ from air pollution. No further correspondence between Hepworth and the Art Bronze Foundry exists after 1971, although the Foundry did later provide remedial work on a cast of Ascending Form in 1996, after her death. Given the spiritual significance of Ascending Form, it is somewhat pertinent that this was the last Hepworth sculpture that the Art Bronze Foundry would work on. Having produced her first bronze in 1956, they would later cast the work which might be considered a memorial to her, sited as it is at the entrance to the cemetery in which she is buried.

While Hepworth continued to work in bronze until the end of her life, completing two major ambitious multi-part works The Family of Man 1970 and Conversation with Magic Stones 1973 in her final years, her output gradually decreased as she suffered from mobility issues brought on from breaking her femur in 1967. As Sophie Bowness notes, from this time onwards she was unable to work in the Palais de Danse much herself – the space associated with the production of her monumental bronzes – and instead, Trewyn became the centre of her working life once again, the studio which she had acquired in 1949 prior to her transition to working in bronze. Of the seven works recorded for the years 1974-5, only two are bronzes (one a maquette), while there are five marble carvings. The age of bronze was coming to an end and in its place white marble was receiving a new renaissance. Even the title ‘Conversation with Magic Stones’ suggests that the bronze upright forms might be seen as standing in for stone. One of her final acts was to order fifteen tons of Carrara marble to be delivered to Trewyn. Sitting in the yard, patiently waiting to be carved, they act as a reminder of all the work she had left to complete.

Dr Clare Nadal

Dr Clare Nadal is a curator and art historian. She completed her PhD at the University of Huddersfield and The Hepworth Wakefield in 2020 on the personal library of Barbara Hepworth, examining the significance that reading held for the development of Hepworth’s art. She has published on Barbara Hepworth for Barbara Hepworth (Musee Rodin, 2019) and Sandra Blow for The Expressive Mark (Stanley and Audrey Burton Gallery, 2021). She is currently working as Programme Co-ordinator at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds and was formerly Assistant Curator at The Hepworth Wakefield, where she worked on the recent retrospective of Hepworth’s work, Barbara Hepworth: Art and Life.

References

[1] The only account of Hepworth’s work with the Art Bronze Foundry to date is that compiled by Sophie Bowness in her essay ‘Barbara Hepworth’s Studio Practice: Plaster for Bronze’ in Barbara Hepworth: The Plasters: The Gift to Wakefield, (London: Lund Humphries, 2011). Matthew Gale and Chris Stephens’ catalogue entries for Hepworth’s works in the Tate Collection also include information on which foundry individual bronzes were cast at, as do the catalogue entries in Barbara Hepworth: The Plasters. See Matthew Gale and Chris Stephens, Barbara Hepworth: Works in the Tate Collection and the Barbara Hepworth Museum St Ives, (London: Tate Publishing, 1999, reprint. 2015).

[2] See Alice Correia, ‘Barbara Hepworth and Gimpel Fils: The Rise and Fall of an Artist-Dealer Relationship’, Tate Papers, No. 22, Autumn 2014 <https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/22/barbara-hepworth-and-gimpel-fils-the-rise-and-fall-of-an-artist-dealer-relationship> (accessed 11.08.22) and Emma E Roberts ‘Representation and Reputation: Barbara Hepworth’s Relationships with her American and British Dealers’, Tate Papers, No. 20, Autumn 2013 <https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/20/representation-and-reputation-barbara-hepworths-relationships-with-her-american-and-british-dealers> (accessed 11.08.22).

[3] Sophie Bowness’ essay in Barbara Hepworth: The Plasters focuses on Hepworth’s relationship with Morris Singer in some depth, see esp. pp. 53-6. Correspondence with Susse Frères was also included in the 2019 exhibition Barbara Hepworth at the Musée Rodin. The correspondence is reproduced in the accompanying catalogue and Sophie Bowness’ catalogue essay also includes some discussion of Hepworth’s work with Susse. See Sophie Bowness, ‘Barbara Hepworth et Paris’, in Barbara Hepworth, (Paris: Editions du Musée Rodin, 2019), pp. 32-42.

[4] Sophie Bowness, ‘Barbara Hepworth’s Studio Practice: Plaster for Bronze’, p. 51.

[5] Jacob Simon, ‘Bronze sculpture founders: a short history’, National Portrait Gallery, 2011 (revised 2017) <https://www.npg.org.uk/research/programmes/bronze-sculpture-founders-history> (accessed 2.07.22).

[6] Jackie Heuman, ‘Glossary of Technical Terms’, in Barbara Hepworth: The Plasters, p. 194. For more on Parlanti and the lost wax process, see Steve Parlanti, The Parlantis: Art Bronze Founders of Fulham, (Leicester: Matador, 2010). Hepworth owned a copy of E.J. Parlanti’s Casting a Torso in Bronze by the Cire Perdue Process (1953).

[7] Jacob Simon, ‘British bronze sculpture founders and plaster figure makers, 1800-1980 – A’, National Portrait Gallery, 2011, updated 2022. <https://www.npg.org.uk/research/programmes/british-bronze-founders-and-plaster-figure-makers-1800-1980-1/british-bronze-founders-and-plaster-figure-makers-1800-1980-a> (accessed 2.07.22). Writing to Hepworth in 1966, Charles Gaskin discussed the works that the Foundry had cast for that year’s edition of the Battersea Open Air Sculpture Exhibition: ‘we did the Miss Frink, Prof. Meadows, Mr. McWilliam Bronzes but alas not the Miss Hepworth and Henry Moore. We are casting reasonably size pieces for Mr. Moore […]’ See Charles Gaskin to Barbara Hepworth, 27 May 1966, Tate Archive, TGA 965/2/11/1/26.

[8] Hepworth had produced a number of bronzes in the early 1920s before abandoning the medium in favour of carving. Some of these early works are listed in her sculpture records, see ‘Volume of Sculpture Records, 1925-8’, Tate Archive, TGA 7247/1, <https://www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/items/tga-7247-1/hepworth-volume-of-sculpture-records/21> (accessed 4.09.22).

[9] Invoice from the Art Bronze Foundry, 8 October 1956, Tate Archive, TGA 20132/5/10/2/1. A work titled Involute is listed on the invoice, probably referring to Involute II which is mentioned in Hepworth’s letter to Gaskin of 7 February 1958 (see TGA 965/2/11/1/1) and listed in records compiled by Michael Gaskin. I am grateful to Philip Freiensener for kindly sharing these notes with me. Involute II was preceded by the earlier bronze Involute 1956. In August 1960 Hepworth wrote to Gaskin to ask him to do ‘6/6 of the large “Involute”’. This seems to refer to Involute II which was cast in an edition of six, unlike Involute which was an edition of seven. See Barbara Hepworth to Charles Gaskin, 24 August 1960, Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

[10] Barbara Hepworth to Kay Gimpel, 25 April 1957, Tate Archive, TGA 20132/2/2/9/62.

[11] Curved Form with Inner Form is listed as costing £225 on an invoice dated 28 July 1960, see TGA 20132/5/10/2/6. Casts of smaller bronzes were cheaper such as Helius which cost £35 when cast in 1956, see TGA 20132/5/10/2/1. The total cost of this receipt is £163 and includes five casts so Hepworth must have sent several further works to the Foundry for casting by the time she wrote to Kay Gimpel in April 1957.

[12] Art Bronze to Barbara Hepworth, 21 September 1971, Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

[13] Invoice from the Art Bronze Foundry, 13 May 1960, Tate Archive, TGA 20132/5/10/2/14.

[14] Invoice from the Art Bronze Foundry, 21 September 1971, Tate Archive, TGA 20132/5/10/2/72.

[15] In a letter to Charles Gaskin in 1966, Hepworth wrote: ‘I have had a great spate of carving during the last twelve months, but I can assure you there will be new works coming along for casting in the near future’. Barbara Hepworth to Charles Gaskin, 31 May 1966, Tate Archive, TGA 965/2/11/1/17. A copy of this letter is also in the Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

[16] Information from Philip Freiensener.

[17] See an unsigned letter from the Art Bronze Foundry from 1961 which states: ‘with regard the large 7ft piece, I would like to see this model before committing myself too firmly.’ Art Bronze Foundry to Barbara Hepworth, 17 October 1961, Art Bronze Foundry Archive. There is no further mention of this work in the correspondence or invoices and in the event it was cast by Morris Singer instead (see Sophie Bowness, ‘Barbara Hepworth’s Studio Practice: Plaster for Bronze’, p. 62).

[18] Jackie Heuman, ‘The Conservation of the Gift’, in Barbara Hepworth: The Plasters, p. 185.

[19] Sophie Bowness, ‘Barbara Hepworth’s Studio Practice: Plaster for Bronze’, p. 53.

[20] Ibid. In 1962 Hepworth told Charles Gaskin that ‘The last few months I have been doing some very large commissions and am only just now beginning to work on a scale suitable to send to you’. Barbara Hepworth to Charles Gaskin, 28 September 1962, Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

[21] Hepworth seems to have asked Gimpel Fils for advice on foundries. In a letter of 1958, Kay Gimpel wrote to inform her that ‘Bernard Meadows has just told me that for big casts, Morris Singer is very good’. Kay Gimpel to Barbara Hepworth, 7 November 1958, Tate Archive, TGA 20132/2/2/9/128.

[22] Barbara Hepworth to Charles Gaskin, 13 October 1961, Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

[23] Barbara Hepworth to Charles Gaskin, 30 October 1961, Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

[24] See for example her letters to Gaskin regarding the casting her 1939 plaster Sculpture with Colour, White, Blue and Red Strings in bronze. Writing in December 1961, she asked Gaskin to ‘proceed with two more copies of small abstract of 1938, ready for me to do the stringing’. See Barbara Hepworth to Charles Gaskin, 11 December 1961, Art Bronze Foundry Archive. Although Hepworth dates the work as 1938 in her letter, it is listed in her sculpture records as 1939 where it is titled Sculpture with Colour and Strings. See ‘Volume of Sculpture Records, 1961’, Tate Archive, TGA 7247/31, <https://www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/items/tga-7247-31/hepworth-volume-of-sculpture-records/40>

[25] Barbara Hepworth to Charles Gaskin, 2 November 1961, Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

[26] The pale blue painted interior of Wave has now largely faded. For further discussion on this, see Alun R. Graves, ‘Casts and Continuing Histories: Material Evidence and the Sculpture of Barbara Hepworth’, in David Thistlewood (ed.), Barbara Hepworth Reconsidered, Critical Forum Series vol. 3, (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press and Tate Gallery Liverpool), p. 176.

[27] Jackie Heuman, ‘The Conservation of the Gift’, pp. 189-90.

[28] Barbara Hepworth to Charles Gaskin, 30 October 1961, Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

[29] Barbara Hepworth to Charles Gaskin, 27 January 1964, Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

[30] Conservation notes compiled by Jackie Heuman and Tessa Jackson note this plaster ‘had been coated with a very thick, shiny layer of lacquer, a finish that is uncharacteristic for Hepworth, and that was probably added during repair work […] it is possible that Patmos was coated with this lacquer to cover up the damage.’ It is unclear whether the application of the lacquer is likely to have changed the colour of the plaster, or whether the current colour is original. See Sophie Bowness with Jackie Heuman and Tessa Jackson, ‘Catalogue of the Plasters and other Prototypes in The Hepworth Gift’, in Barbara Hepworth: The Plasters, p. 132.

[31] Barbara Hepworth to Charles Gaskin, 27 January 1964, Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

[32] Barbara Hepworth to Charles Gaskin, 29 December 1961, Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

[33] Barbara Hepworth to Charles Gaskin, 5 November 1962, Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

[34] Barbara Hepworth to Charles Gaskin, 30 October 1961, Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

[35] Jackie Heuman, ‘The Conservation of the Gift’, p. 190.

[36] Information from Philip Freiensener. I am very grateful to him for this important insight.

[37] Sophie Bowness, ‘Barbara Hepworth’s Studio Practice: Plaster for Bronze’, p. 57, p.92.

[38] Hepworth’s secretary Miss Moir wrote to Charles Gaskin in 1969 to notify him that ‘it was ‘milk white’ that the previous casts of “Ascending form” were done and [Barbara Hepworth] would like to have this cast just the same as it has been most satisfactory’. See Miss Moir to Charles Gaskin, 20 January 1969, Tate Archive, TGA 965/2/11/130. A copy of this letter is also held in the Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

[39] Laura Davies, ‘Observing Hepworth: A Conservator’s Perspective’, Hepworth Research Network Launch, The Hepworth Wakefield, 12-13 March 2020 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l9fWSr9lwoQ&list=PLdCi_qvG_1dHatFPARJfRWMlRLZ-YL9dm&index=38> (accessed 11.08.22). Sculpture Conservator Melanie Rolfe notes that ‘the deliberate application of colour to the surface of finished bronzes is almost always by means of chemical patination which is achieved by the application of chemical salts in solution to the surface of the bronze. […] The resulting patinas are usually black, brown and greens of varying hues.’ See Melanie Rolfe ‘Colouring Sculpture – Material Evidence from Barbara Hepworth’s Working Spaces in St Ives’, Hepworth Research Network Papers, <https://hepworthwakefield.org/our-story/hepworth-research-network/papers/> (accessed 12.08.22).

[40] Jackie Heuman, ‘The Conservation of the Gift’, p. 191.

[41] Studio St Ives seem to have regularly photographed Hepworth’s plasters as well as her finished bronzes. Examples are reproduced in both Barbara Hepworth: The Plasters and in Sophie Bowness, Barbara Hepworth: The Sculptor in the Studio (London: Tate Publishing, 2017).

[42] See Michael Kennedy, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music, third edition, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980), p. 258.

[43] Edwin Mullins, in Barbara Hepworth, (Hakone: Hakone Open-Air Museum, 1970), n.p. qtd. in Gale and Stephens, Barbara Hepworth: Works in the Tate Collection, p. 179.

[44] Gale and Stephens, Barbara Hepworth: Works in the Tate Collection, p. 181. For further discussion of the role of religion in Hepworth’s work see Lucy Kent, ‘An Act of Praise’: Religion and the Work of Barbara Hepworth’, in Penelope Curtis and Chris Stephens (eds), Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World, (London: Tate Publishing, 2015), pp. 36-50.

[45] Michael Gaskin to Barbara Hepworth, 9 June 1971, Tate Archive, TGA 965/2/11/1/46. A copy of this letter is also in the Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

[46] ‘Certificate of Destruction, 24 September 1971’, Tate Archive, TGA 965/2/11/1/50. A copy of the certificate of destruction is also in the Art Bronze Foundry Archive. It was Hepworth’s practice to request that original casts were either returned to her or that foundries provided certificates of destruction to prevent further casts being produced without her permission. See Sophie Bowness, ‘Barbara Hepworth’s Studio Practice’, pp. 62-3.

[47] Michael Gaskin to Barbara Hepworth, 9 November 1971, Tate Archive, TGA 965/2/11/1/53. . A copy of this letter is also in the Art Bronze Foundry Archive.

[48] Sophie Bowness, Barbara Hepworth: The Sculptor in the Studio, p. 66.

[49] See Barbara Hepworth, ‘Volume of Sculpture Records, 1974-5’, Tate Archive, TGA 7247/45 <https://www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/items/tga-7247-45/hepworth-volume-of-sculpture-records/9> (accessed 14.08.22). By comparison, twenty-one works are recorded for the year 1970.

[50] Sophie Bowness, Barbara Hepworth: The Sculptor in the Studio, p. 70.