I start with an idea or sensation and finish with an object - an image which will be kept or destroyed.

This apparently rather stark statement by Turnbull from quite early in his career is in fact a very succinct encapsulation of his sculptural practice, summing up the inspiration, execution and critical rigour that have made him one of the most significant and distinctive British sculptors of the Post-war period.

His early story is not dissimilar to that of many of his generation; early artistic interest and promise interrupted by WWII and a return to civilian life coinciding with a great growth of interest in new forms of art. Enrolled at the Slade initially as a painter, he found the atmosphere too retrospective and shifted to the Sculpture department.

Whilst sculpture at the Slade followed generally traditional paths, it was less hidebound than other disciplines and alongside his fellows Eduardo Paolozzi and Nigel Henderson, Turnbull was able to explore his interest in contemporary continental ideas which had challenged the orthodox approaches to material, techniques, sources and indeed the basic raison d'etre of sculpture. He moved to Paris in 1948, then still the city at the hub of artistic and intellectual life in Europe, and along with Paolozzi, new directions and influences become clear in his work.

© William Turnbull

Blade Venus 4, 1989, Bronze on a York stone base, Edition of 6, © William Turnbull

David Wade Fine Art Ltd. acquired on behalf of a private collector

Turnbull's ability to create objects that are both of the present yet also enduring has been a feature of his work from its earliest days, but in the sculpture of the latter part of his career we see this very clearly.

© Alberto Giacommeti

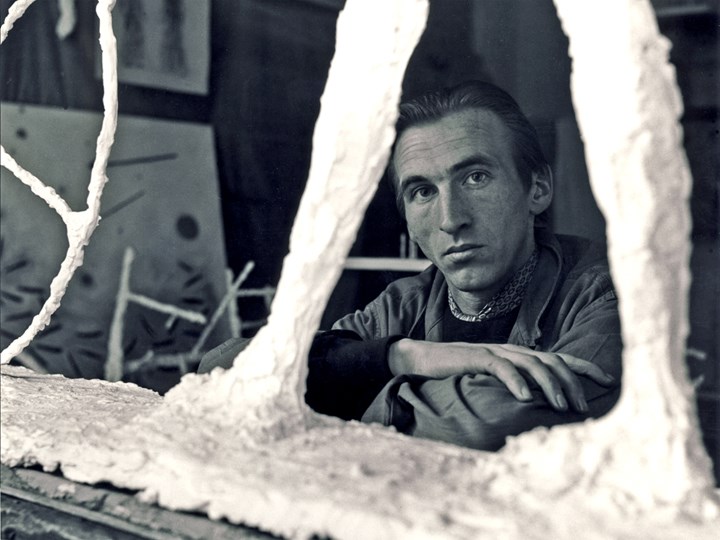

Turnbull became familiar with a number of artistic giants in Paris, notably Brancusi and Leger, but he came to know Alberto Giacometti particularly well. Already a key figure in the surrealist world between the wars, Giacometti had lately begun to explore a new sculptural language that was infused with the existential philosophical concerns of a world recovering from extreme warfare. Turnbull found in his own use of anonymous but evocative forms a vocabulary that gave his sculpture an ability to be both representational and abstracted, creating objects that could step outside their immediate reality and take on a wider, deeper meaning.

Turnbull was part of generation of British sculptors quite unlike any that had preceded it, a generation whose work reached an international audience and achieved huge acclaim. The launchpad for them was a small side exhibition at the 1952 Venice Biennale, New Aspects of British Sculpture, the supporting act to the much-feted Graham Sutherland's retrospective[2]. Although each sculptor's individual presence was quite limited, the overall effect of their work was to awaken a new interest in the potential of these young artists.[3]

Whilst there are superficial similarities between their works, we can now see clearly that contemporary claims of a collective consciousness were perhaps exaggerated[4], and although Turnbull's early work did indeed make use of rather etiolated and skeletal forms, there is very little sense of the angst and despair which is sometimes attributed to his peers. Indeed, the sense of playfulness in these works, of lightness and balance demonstrate another contemporary interest for Turnbull, the work of the painter Paul Klee whose delicate and unusual compositions were extremely highly thought of in post-1945 Britain.

Turnbull was part of generation of British sculptors quite unlike any that had preceded it, a generation whose work reached an international audience and achieved huge acclaim.

If we fast-forward four decades to 1989, the year in which Blade Venus 4 was made, it is easy to see how the germ of this sculpture lies in that fertile post-war Parisian earth. Concepts of metamorphosis, of suggestion, take these later works into another world, one where we find our recognition of apparently familiar and identifiable forms subverted by a curious sense of timelessness.

The apparent lightness of this sculpture, never an easy task with a heavy metal object standing well over one and a half metres tall, and the differentiation in form and character from alternate viewpoints immediately confront the viewer, drawing us to a piece which amply demonstrates that simplicity can be a very complex thing. Turnbull's sources for his later sculpture, such as Blade Venus 4, were in the world around him. Tools, surfboards or, as here, a knife blade and tang are just the starting point for a journey of transformation.

Turnbull's ability to create objects that are both of the present yet also enduring has been a feature of his work from its earliest days, but in the sculpture of the latter part of his career we see this very clearly.

His understanding of ancient sculpture, of the metamorphosis from material to idol, informs every step of his work. Poised on its tip, Blade Venus 4 cannot but make us constantly aware of its delicate balance, the sense that it might be on the verge of movement as clearly as an Ancient Greek kore figure may seem on the verge of speech[5]. Its surface appears rough-hewn yet the curves that so delicately delineate the form cut exquisitely through the space that the sculpture occupies. Blade Venus 4 is at once a familiar object, yet presented as it is, of almost human scale, balanced and waiting, it assumes a mantle of otherness, something that seems strangely primal.

Although each sculptor's individual presence was quite limited, the overall effect of their work was to awaken a new interest in the potential of these young artists.

Large Blade Venus, 1990, Chatsworth House

© William Turnbull

One of the great challenges for abstraction in the twentieth century was to discover a visual language in which the viewer would not, or could not, find forms reminiscent of the natural or man-made world. Whilst being apparently abstract, Turnbull's work embraces the reality of the source but represents that same source in an unexpected way, thus revealing the solid foundations of his art yet still allowing us to bring our own imagination to it. Like a found pebble or branch whose form seems to mirror something else, Blade Venus 4 challenges us to find both its actual roots and our own interpretation of how such a thing can captivate the space around it.

What do we expect from a piece of sculpture? There is, one might say, sculpture and sculpture. It can be a simple three-dimensional rendering of some aspect of the natural world in a semi-immutable material such as wood or bronze. It may simply be an object which decorates a place, making no demands on us. Or it may be something else quite different, an object that goes beyond the concept of likeness or decoration towards a state where it can affect the space it inhabits and thus those who come into contact with it. Like a primitive totem, Turnbull's sculptures invite our participation in their existence, yet they also keep us at bay. The surface, so delicately coloured and tempting to touch, draws us in close, while the seeming impossibility of the perpetual balancing act that the piece is performing reminds us to keep our distance. The apparent simplicity of its form belies the complex harmonies within the geometry that underpins it; they are seemingly of our world but also not.

Turnbull's sculpture has retained its fascination for well over sixty years now. Unlike the work of some of his contemporaries, it still appears remarkably fresh and of the moment, and the qualities which give it such a distinctive voice do not feel rooted in any time or place. His sculptures offer a concentrated experience, an engaging experience, an elusive experience, and for those lucky enough to own one, a rewarding experience.

Unlike the work of some of his contemporaries, it still appears remarkably fresh and of the moment, and the qualities which give it such a distinctive voice do not feel rooted in any time or place.

References:

[1] William Turnbull, Statement, in Contemporary British Sculptors, exh.cat., The Arts Council, 31 May - 30 August 1958

[2] We can now see that Sutherland was, in 1952, at the zenith of his career artistically. Although there would be many years of commercial international success ahead of him, his achievement of the 1935-1955 period stands as a major landmark in the British artistic map of the middle years of the twentieth century.

[3] The eight sculptors included were Robert Adams, Kenneth Armitage, Reg Butler, Lynn Chadwick, Geoffrey Clarke, Bernard Meadows, Eduardo Paolozzi and Turnbull. Every one of them would go on to achieve a significant international reputation during the 1950s and 1960s.

[4] Herbert Read's introductory essay for the exhibition catalogue contributed a good deal of this, and gave us the 'geometry of fear' label under which all these sculptors have to some extent laboured throughout their careers.

[5] Turnbull had drawn on Ancient Greek sculpture in his earliest work, with the Hera of Samos, circa 570-560 B.C. (Louvre, Paris), being a particular influence on his series of standing figure/standing form pieces of the mid 1950s.